It has been a tough year for the winemakers of the Bergerac. The frosts and hail of this spring and the wet early summer combined with dire shortages of labour in the unusually late season for picking the grapes to give vineyards endless headaches.

My friends at Chateau Feely in the Saussignac report that last year half the grapes were in by the end of August. This year, they only reached that stage on September 22, but that was because of the late maturing on the grapes rather than labour shortages. But other vineyards have found that picking in September meant that many mothers of school age children who could work long hours in the school vacations found it tougher once school started.

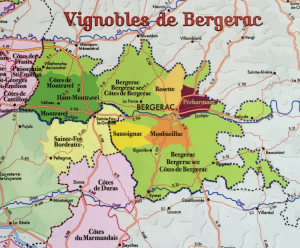

Benoît Gérardin of Château Le Fagé had only 14 grape pickers this year instead of the usual 25, and shortage were common throughout the Monbazillac region. The pickers, he complained to the media, were signing up for several different vineyards but only turning up for those offering the most pay for the fewest hours. Worse still, they were signing up for the St Emilion vineyards where the harvest season was later than usual and the pay was higher.

The good news, however, is that this year’s wine looks to be very good for quality, if not too generous in quantity. And this will be wine as it used to be twenty and thirty years ago, with only 12 or 13 degrees of alcohol rather than the 14 and 15 degrees that has become more common with the hotter summers of climate change.

Moreover, the revolution has begun. The French wine bureaucracy has at last responded to climate change by accepting that the appellation controllée system had to be modified to adapt to climate change.

The most dramatic shift has been in the crucial Bordeaux region, where some two-thirds of the wine comes from the Merlot grape. Warmer summers mean that the grapes now become ripe in August, two to three weeks before the tannins and phenols have had the time they need to mature. So to get those crucial tannins, the grapes stay on the vine until they are bursting with sugar, which means they are also producing much more alcohol. That is why the amount of alcohol in wines has been steadily increasing.

‘I began making wine twenty years ago,” says Xavier Grassies, cellarmaster at Château Morillon (Campugnan/Blaye).. “Back then, we produced wines at 12.5 percent and sometimes we even had to chaptalize (adding sugar) to the juice to increase the alcohol content. In the last ten years or so, everything has changed: nowadays, it is rare to produce a wine below 14.5 percent.”

The average temperature in the Gironde department has increased by 1.5°C in the past thirty years. The impact is already visible in the vineyards, with shorter growth cycles, overripe grapes, earlier harvests and higher alcohol contentsAs a result, the INAO (French National Institute of Origin and Quality) has approved the introduction of six new grape varieties for climatic and environmental adaptation in the Bordeaux region. From now on, they may be planted by winegrowers, but so far only on an experimental basis.

‘We are currently witnessing a paradigm shift: we now have to contend with excess temperatures and low rainfall,’ notes Alexandre Pons, a research scientist at the University of Bordeaux. ‘We have to rethink our entire operations both in the vineyard and cellar. In other words, we must change everything in order to keep everything the same.’

The work on adaptation began come years ago at a test plot owned by the National Institute for Agricultural Research in Villenave d’Ornon, planted with 52 French and foreign grape varieties in 2009 to analyse the way the vines adapted to warmer summers but also, (and this sounds ominous) to evaluate their physiological response to drought.

Six grape varieties were chosen from this plot (four reds and two whites) to be introduced on an experimental basis by the Bordeaux and Bordeaux Supérieur areas. But grapes that were deemed too distinctive or too far removed from the classic Bordeaux wines were not included. So no vines from Alsace or the French Mediterranean regions, and no classic local versions like the Syrah vines of the Côtes du Rhône.

So planting is now under way of vines that few if us have heard of. At Chateau Roquefort in Lugassan they are not renewing their Merlot wines on the limestone plateau but planting four thousand wines each of Castets and Atinarnoa. Do not expect to be drinking the results soon. A lot of experiments are planned to see how these wines develop and adapt, whether they are suitable for blending and so on.

These grape varieties are authorized to represent up to 5 percent of the area planted with vines, and up to 10 percent of the final blend of a given wine, and must not be mentioned on the bottle label.

At Chateau Morillon, they have planted Marselan, a grape that produces good quantities of rich and flavourful wines that have relatively low levels of alcohol. Xavier Grassies at Morillon it to develop the wine not in barrels but in clay amphorae and expects to emerge tasting like a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon and Grenache.

Similar experiments are under way in the Bergerac, where we have the advantage of being able to bring back some of the traditional vines that were grown here before the phylloxera epidemic of the late 19h century, like the Merille Noir grape, sometimes known as Perigord.

And new varieties are not the only answer, in part because the scientists are wary of changing the familiar character of Bordeaux wines. So they are also working with historic vines that fell into disuse, like Carménère, Malbec and Petit Verdot.

The four red grape varieties being tried are:

Arinarnoa: the result of a cross between Tannat and Cabernet Sauvignon. Low sugar levels and good acidity. Produces well-structured, deeply-colored, tannic wines with complex, long-lasting aromas.

Castets (originating in Southwest France): historic grape variety overlooked in the Bordeaux region. Fairly resistant to gray rot and powdery mildew and very resistant to mildew. Produces deeply-colored wines with good aging potential.

Marselan, a cross between Cabernet Sauvignon and Grenache. A late-ripening grape variety, fairly resistant to gray rot, powdery mildew and spider mites. Produces high-quality, distinctive and deeply-colored wines with good aging potential.

Touriga Nacional (originating in Portugal): a very late-ripening grape variety, less exposed to spring frosts. Fairly resistant to fungal diseases, except for dead arm disease. Produces high-quality, complex, aromatic, full-bodied, well-structured and deeply-colored wines with good aging potential.

The two white grape varieties:Alvarinho (originating in Spain): pronounced aromatic qualities that counterbalance the loss of aromas caused by climate change. Fairly resistant to gray rot. Average sugar levels which help produce fine, aromatic wines with good acidity.

Liliorila, pronounced aromas, like Alvarinho. Produces powerful, aromatic wines.