Beverly Held, Ph.D. ‘aka Dr B’

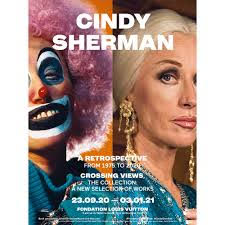

Figure 1. Cindy Sherman Exhibition Poster, Foundation Louis Vuitton, 2020

Do you know Cindy Sherman, the American photographer? She is currently the subject of a grand retrospective at the Foundation Louis Vuitton. Sherman’s subject has been, since the beginning, that is since 1975, almost exclusively, herself. And so, I thought it was a very clever idea that the exhibition space incorporates mirrors.

(Figure 2) You are most likely familiar with the English art historian John Berger’s slender volume entitled Ways of Seeing (1972). If not, I urge you to read it or watch the 4 part BBC television series. One chapter is about the mirror, and a little section is about how startling and discomforting it is when we happen upon a mirror unexpectedly. And that is what happened to me when I came upon the first mirror in the exhibition. But once I realized that the first mirror wasn’t the only mirror, I decided the best way to proceed was to anticipate the mirrors, to prepare myself for them and to pose for them and for myself, each time it happened, which was often. I also watched other people, to see how they responded, reacted - some looked away, others lingered, stopping to fine-tune their appearance before moving on, as one does. (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Exhibition space with mirror reflection

The exhibition was, as Sherman’s work is, divided into themes. One writer noted in his review of the Sherman retrospective held the National Portrait Gallery in London last year, that Sherman’s work recalls Jean de La Bruyère’s 1688 Caractères ou les Mœurs de ce siècle La Bruyère’s book is an encyclopedia of French society under Louis XIV. His chapters are arranged thematically under such topics as 'Women' 'Great People' and “Fashion”. Cindy Sherman’s photography is a thematically arranged encyclopedia of contemporary North American society, with many of the same topics. La Bruyere lived in a book civilization, he wrote a book. Sherman lives in an image civilization, she makes photographs.

In considering Sherman’s uncanny ability to mimic images from disparate sources, another writer looked to nature. “Mimicry in nature,” he tells us, “was first observed in butterflies”. Certain butterflies camouflage themselves as wasps; others as their poisonous brethren. According to the novelist Vladimir Nabokov, “when butterflies masquerade as leaves, their disguise includes the small holes chewed by grubs.” What predator, Nabokov asks, could appreciate the subtlety of these “non-utilitarian delights” . For Nabokov, it was for the art. So too for Cindy Sherman.

As we know, some female artists began their careers as models, like Suzanne Valadon (mother of Maurice Utrillo) and Lee Miller (mistress/colleague of Man Ray). But Cindy Sherman has been, from the beginning, since 1975, when she was 21 years old, both artist and model. She creates the art and she is the raw material from which the art is created. She is the actor and the acted upon, the gazer and the object of the gaze.

The earliest photographs for which Sherman is known are her ‘Untitled Film Stills’. None has a name, but each has a number, as for example “Untitled #_”. The beauty of this method, which has been consistent throughout her career, is that the viewer is free (obliged) to decide what the photograph depicts, what it refers to, even what it might mean. Giorgio de Chirico wanted to be enigmatic, so he used the word ‘enigma’ in the title of some of his paintings. An easier way to be enigmatic, it seems to me, is simply not to give your work a title and let the viewer find his or her own interpretation or not.

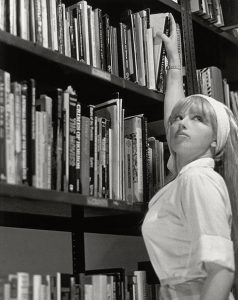

The ‘Untitled Film Stills” that Sherman created in the late ‘70s, evoke film heroines of the 1950s, Kim Novak, Bridget Bardot, Gena Rowlands, etc. Sherman’s photos are direct references to the ‘publicity stills’ typically shot onset and used to advertise a film. But Sherman’s ‘Untitled Film Stills’ don’t reference any particular film or film star. She plays with stereotypes. In Untitled Film Still #21, (Figure 3) she is a young career girl in a new suit on her first day in the big city’ (to me, she is Mary Richards, from the Mary Tyler Moore show, a little apprehensive but, ‘she’s going to make it after all’ (Figure 4 ). In #13, she is a sexy librarian standing against a wall of books wearing a crisp white shirt.(Figure 5) She pulls a book entitled “The …. Dialogue” from a high shelf. The headband she wears echoes the one worn by Brigitte Bardot in Contempt. (Figure 6) But here, as with other images in this series, even if the viewer thinks they can spot a direct correlation, there really isn’t one. The connection relies upon the background and knowledge that Sherman’s viewers brings with them. In all of these ‘Untitled Film Stills’, Sherman is creator, director, actor, costume designer, technician, prop master, and artist.

Figure 3. Untitled Film Still #21

Figure 4. Opening credits for Mary Tyler Moore Show

Figure 5. Film Stills #13

Figure 6. Brigitte Bardot in Contempt, 1963

In the 1980s, Sherman moved on to “Rear Screen Projections” placing herself in front of a screen on which a scene is depicted. (Figure 7) More possibilities, less props. These screens had been a common special effect in films. It was versatile, it was cheap. No need to travel to locations, no need to build sets. Scenery rolled along, while the actors stood or sat still. Hitchcock was a fan and I am sure you can, as I can, remember Grace Kelly and Cary Grant in To Catch a Thief, (Figure 8) sitting in a car, looking ridiculous (to us), because the car is not moving even though the scenery behind them is rolling by. For Sherman, these Real Screen Projections were a way to continue exploring stereotypes of women in film, while expanding the possibilities of representation. Typically, Sherman poses in front of a scene that is blurred or hazy while her own image is clear, distinct. The format is larger than the first series and she is now working in color, which she will continue to do for the rest of her career.

Figure 7. Rear Screen Projection

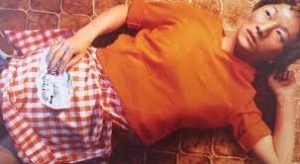

In 1981, Artforum commissioned Sherman to create a series of photographs. She called these images, ‘Centerfolds,’ an obvious reference to the centerfolds in magazines like Playboy. (yes, I read it for the interviews, too) But Sherman’s women aren’t posing provocatively. Each is alone, manifesting a particular emotion, terrified, angry, pensive, sad, but not seductive. (Figure 9) They are unlike Playboy’s women in lots of ways, chief among them, they are dressed.

Figure 9. Centerfolds

But the editor of Artforum refused to print these photographs, explaining that she was afraid that the series would be misunderstood by militant feminists since they looked “a little too close” to the pinups in actual men’s magazines. As Calvin Tomkins noted in The New Yorker, they were, “misunderstood by a number of political-minded art students (male and female), who accused Sherman of undermining the feminist cause by depicting women in ‘vulnerable’ poses.”

Sherman wrote about this series: “I wanted to fill this centerfold format, and the reclining figure allows you to do that. But I also wanted it to be something in the sort of feminist realm, you know, you open it and see a woman lying there, and you then look at it closer and suddenly realize, ‘Oops, I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to invade this private moment.’ … I was definitely trying to provoke in those pictures. But it was more about provoking men into reassessing their assumptions when they look at pictures of women. I was thinking about vulnerability in a way that would make a male viewer feel uncomfortable - like seeing your daughter in a vulnerable state.”

It was Untitled #93 (Figure 10) that provoked the most controversy. Some people saw the young woman lying there, with the covers pulled up, her bra straps showing, her empty stare, her disheveled hair, as a ‘post rape’ scene. Sherman said that she thought of it as a young woman who had been out all night partying and who had just been awakened by the sunshine too soon after she had fallen asleep.

Figure 10. Centerfolds, Untitled #93

That people who were really trying to ‘read’ the image, came up with such completely different interpretations shows how rich the image was for exploration. That in the cultural landscape of the time, the editor was unwilling to include the prints shows that our present moment of walking on eggshells trying not to offend, is nothing new. Currently, the brouhaha in the art world is the postponement of the Philip Guston retrospective. This American artist included figures of Klansmen in his work because he hated and feared them. (Figure 11) One museum director said they were postponing the retrospective because now is not the time for white artists to be explaining racism. I guess ‘white-splaining’ is every bit as inappropriate as ‘man-splaining’.

Figure 11. Philip Guston

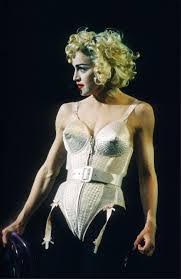

Let’s lighten this up a bit shall we and move to high fashion. Sherman tells us that 'in the mid-'80s, I did some stuff for this boutique in SoHo, Dianne B. It was really early Comme des Garçons, Castelbajac, Gaultier. It was the weirdest stuff, especially the Comme. I was like, 'This looks like bag lady clothes'—holes in it, ripped up, pirate-y. Kind of ugly, jolie laide” Dianne Benson, who owned this very upmarket boutique had asked Sherman to shoot an ad campaign. Benson gave Sherman carte blanche, she could “take anything” from the store, and “do anything” she liked with it. Sherman took, among other items, two cone bras by Jean-Paul Gaultier. They pop up again (to excuse the expression), as you may remember, when Madonna made them famous on her Blonde Ambition tour. (Figure 12) Madonna wore them in the way Gaultier intended, as protruding cones, Sherman, not surprisingly, inverted them. (Figure 13)

Figure 12. Madonna, Blind Ambition Tour, wearing Gaultier

Figure 13. Fashion Shoot, in Gaultier

In the early 90s, Sherman began to work with Harper’s Bazaar. She was given the same mandate that Dianne Benson had given her. According to Sherman, 'They sent tons of clothes to my studio and said, 'Do what you want.' And since Sherman had always been interested in fashion photography, she was happy to comply. Sherman did not follow in the footsteps of Richard Avedon at Harper’s or even the quirkier footsteps of Man Ray for the same magazine. Instead, Sherman eschewed beauty and elegance for sunburns and awkward poses. A couple years later, for Comme des Garcons, she used dolls and prosthetics and heavy, theatrical makeup for a fashion shoot. And for a series of photographs for Balenciaga, she became a series of ‘types’ like “fashion victim” and “aging party girl”. (Figure 14)

Figure 14 .Fashion Shoot, in Balenciaga

Unlike Avedon and Man Ray, Sherman doesn’t set out to create a glamorous image or to place emphasis on the clothes she was ostensible photographing. Her ads tell stories. She becomes characters in scenes that must be interpreted by the viewer. Sometimes the clothes are shown to advantage, sometimes not. The scenes are always arresting, if not alluring. Since her first collaborations nearly 40 years ago, the terms have remained the same. She selects or is given clothes to work with. The images she creates are both for the entities that commission them and for herself. How do Sherman’s terms differ from those which Man Ray had with the same entities? Man Ray, you will remember, intentionally produced as few photographs as possible for the fashion magazines because whatever he created for them, they owned, photograph and negative. Sherman seems to have cut a better deal for herself. To put it another way, Cindy Sherman seems to work WITH fashion houses and fashion magazines, Man Ray worked FOR them.

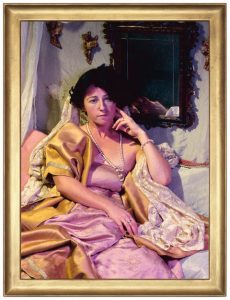

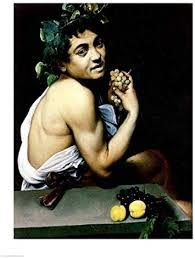

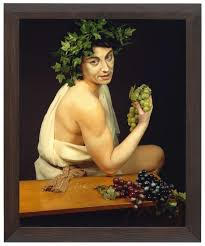

As she was working in fashion, she dabbled in history. It was with those photographs in which she imaged / imagined herself as a subject taken from the canon of western art history that her work began to sell, that she began to make money. Sherman says, “I didn’t start to feel super-successful until I did the paintings show (the History Portraits), I think they sold because they looked like old paintings.” Let’s look at a few of Sherman’s ‘takes’ on the Old Masters. She selected paintings from the mid-1440s through the mid-1840s, from Jean Fouquet’s Melun Diptych (Figure 15, Figure 16) through Caravaggio’s Sick Bacchus to Ingres Madame Moitessier. (Figure 17, Figure 18) With the Fouquet and Ingres, you can see Sherman playing with and riffing off the original without being in any way tied to them. But with Caravaggio, Sherman has met her match. (Figure 19, Figure 20) His Bacchus is already scruffy. His face is already lined. Dirt is already under his fingernails. Sherman’s work is closer to a literal translation than with anything else she has done, it is an homage, from one medium to another, an appreciation by one artist for another.

Figure 15. Jean Fouquet, Melun Diptych, 1450

Figure 16. Cindy Sherman, after Fouquet

Figure 17. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Mme Moitessier, 1850

Figure 18. Cindy Sherman after Ingres

Figure 19. Caravaggio, Sick Bacchus 1591

Figure 20 Cindy Sherman after Caravaggio

Apparently, creating images that pleased people made Sherman feel ‘guilty’ so she started a provocative series right afterwards, her ‘Sex Pictures’ which are as difficult to look at as her earlier Disasters series and neither series includes the artist’s own image. The Disaster Series is the visible remains of, well, of disasters - body fluids and the like. The Sex Pictures are anatomical models in sexually explicit poses. I think we can pass on those here, but you can whet your curiosity by googling either or both.

In the early 2000s, right after 9/11 when she was wondering what the point of making art was, Sherman created her Clown Series. (Figure 21) These are not the clowns that anyone’s parents invite to their child’s fifth birthday party, that’s for sure. Sherman said, “I thought that clowns would have a limitless vocabulary … not just irony or humor, but also pathos and tragedy.” And like Sherman suggests, who knows, under all that make-up and artifice, these clowns might easily be murderers and rapists. Has anyone seen the Netflix series ‘The Good Place’? Looking at these clowns, I couldn’t help but think of poor fake Eleanor, (Figure 22) with that nook, filled with pictures of clowns that terrify her.

Figure 21. Clown Series

Figure 22. ‘The Good Place’ Clowns & Eleanor

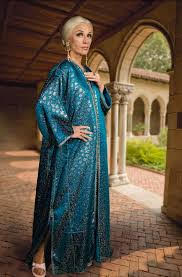

Four years after Clowns, Sherman tackled another sort of clown, a heavily made up older woman trying to cosmetically hide the ravages of time. Called ‘Society Portraits’ Sherman dons evening dresses and caftans, strikes elegant poses in front of equally elegant dwellings. But there is always a tell tale sign or two or three that the adversary is winning, that it is not possible to deter the steady march of time. Sometimes it is the wrinkles evident under too thick make-up, or as in Untitled #466, (Figure 23) it is a glimpse at the sheen of compression stockings and the cheap plastic sandals called upon when feet are too swollen to fit into designer mules. Sherman credits / blames her high resolution camera for this series, how the changes in her own face were more obvious to her because of that camera. She writes, “What disturbs me, is not seeing more wrinkles on my face but realizing that my opportunities are much more limited. I could look a hundred years old if I wanted to, but looking younger than fifty is an absurd idea” That seems a little extreme to me, after all, she wrote it 12 years ago when she was just 52. Seems to me that she is looking forward to the new possibilities that an aging face will bring rather than bemoaning the loss of her younger face.

Figure 23. ‘Society Portraits, Untitled #466

A few years ago (2016) for a Harper’s Bazaar shoot, she portrayed herself as a fashion groupie, (Figure 24) you know, those young women who parade around Manhattan or wait outside a fashion show hoping to be noticed, indeed hoping to be photographed, preferably by Bill Cunningham for all the years he did exactly that. Did you ever see his column On the Street in the Sunday Style Section of New York Times? For On the Street, Cunningham’s focus was on clothing as personal expression. He explained it this way, 'I am not fond of photographing women who borrow dresses. I prefer women spend their own money and wear their own dresses.... When you spend your own money, you make a different choice.” Hilton Als described it like this in The New Yorker, 'He loved 'the kids,' who wore their souls on sleeves. His fashion philosophy was populist and democratic.” My daughter and I saw Cunningham a few times taking photographs in Paris during Fashion Week. Ostensibly there to photograph the runway models, he was just as busy photographing the mostly young, mostly bizarrely dressed women who solicited a photo by him in the hopes of appearing in the NYT. He genially complied and took photo after photo of those young women. Some of those young women, bloggers and influencers, brought their own photographers to make sure their followers would see them modeling at Fashion Week.

Figure 24 ‘Fashion Groupie’

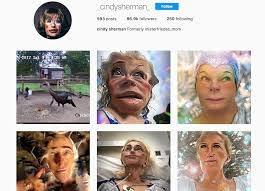

Initially repulsed by the selfie, which Sherman called vulgar, (seems a little odd since on some level Sherman is the mother of all selfies), Sherman has come to terms with it and indeed has become rather prolific on Instagram. Rather than use the apps to make herself look better, she uses them to distort and play with her image. (Figure 25)

Figure 25. Instagram

The final group of photos are those she began taking just last year for Stella McCarney, the fashion designer (and Paul’s daughter), for her new men’s wear line. Let me describe just one of the photos because it is as good a way as any to end this discussion. A man (Sherman is mostly men for this series, it is the men’s line after all) of indeterminate age, wearing a camel sports jacket that is a bit too big for him, stands in front of a very fake, very manicured exterior. His hand in his pants pocket, he gazes out, sort of looking at the viewer. (Figure 26) Underneath the sports jacket is the piece de resistance. It is a teeshirt with Sherman’s own image on it, from the very first series she did. It is Untitled #74 (Figure 27) from her Stills series, a ‘Hitchcockian heroine in a canary yellow coat”. So, we have come full circle and end with Cindy quoting Sherman, branching out, looking forward without hesitation, seeking new opportunities to master new skills and depict herself in new and different ways.

Figure 26. Stella McCarney Menswear

Figure 27. Film Stills Series, Untitled #74