A Life in Art / An Artful Life

Beverly Held, Ph.D. aka ‘Dr. B.’

In 1780, John Adams was in Philadelphia, his wife was in Massachusetts. In one of his many letters, he wrote the following, “I must study politics and war, that our sons may …study…commerce and agriculture in order to give their children a right to study painting, …architecture (and) statuary…..” And how do the musings of the second president of the United States relate to the subject of the book under review? Let’s see.

Bernard Berenson A Life in the Picture Trade, by Rachel Cohen, is, as the title suggests, a book about a man who made pictures, paintings, his life. Wait, don’t go. This book is filled with so many nuggets of nuanced observation that I know you will find the lucky twists and unfortunate turns of Berenson’s life as interesting as I did. The author’s success lies not only in her ability to bring to life a life but to bring to life the mores and morals of the times and places in which Berenson flourished and floundered.

So, Bernard Berenson. Have you ever heard of or visited the Villa I Tatti, Harvard’s Center for Renaissance Studies tucked into the hillside above Settignano, 10 minutes from Fiesole, 15 minutes from Florence. The villa, its artwork, its library and its gardens were bequeathed to Harvard University by Bernard Berenson. Based upon John Adams calculations, Berenson must have been the grandson of a politician and the son of a businessman. Obviously, he must have been born into money. How else to explain the villa, the art, the books? Yet the answer to all of the above is no, no and no. And therein lies the tale that Rachel Cohen tells so masterfully in this biography.

To begin, like so many people who emigrated from Eastern Europe to America, Bernard Berenson’s name was not Bernard Berenson ‘in the old country’. Bernhard Valvronjenski was born in 1865, in Lithuania, in Butrymaney, in the Pale of Settlement (which always makes me think of Evita Peron’s ‘back of beyond’), to one family amongst many, indeed one amongst five million Jews who were permitted to reside there but who barely survived there. With no freedom of movement and no permission to grow crops, hunger was a constant companion, starvation a constant fear. In the years right after Bernhard was born, a commission appointed by the governor-general of Vilna, the largest and nearest town, declared that the Jews were a “contemptible and abominable nation”. Those sentiments were shared rather broadly. Berenson’s grandmother, whom he adored, who cared for him like her own because her daughter, his mother, was still a child herself when Bernhard was born, died when Bernhard was 4, perhaps of starvation. A few years later, the family’s house burned down - accident, maybe, arson, likely. Not being amongst the optimists, those Jews who thought that the situation would improve, the Valronjsenski family decided it was time to try their luck in America. Bernhard’s father went first, a third class ticket on a steamer bound for Boston. Cousins of his were already there. The next year, Bernhard, his mother and two younger siblings, followed him.

It saddened me to read about Bernhard’s father, an intellectual who enthusiastically embraced secular Judaism. He hadn’t worked in Lithuania, perhaps because he had not been trained to do anything, perhaps because there was no work a Jew was permitted to do. For a learned man with no business acumen (and he had none), there was no path forward in Boston, either. Rachel Cohen tells us he was a peddler who worked for his cousin who owned a scrap metal and tinware shop. At the end of every day, we are told, he would bring the scrap metal he had collected to his cousin’s shop. It sounds like back breaking and soul numbing work. And it sounds identical to Kirk Douglas’s (Issur Danielovitch) father’s job. According to Douglas, “My father, who had been a horse trader in Russia, got himself a horse and a small wagon, and became a ragman, buying old rags, pieces of metal, and junk for pennies, nickels, and dimes … Even … in the poorest section of town… the ragman was on the lowest rung on the ladder. And I was the ragman's son.” Bernhard Berenson was the Tin Man’s son, which had nothing to do with the Wizard of Oz, I am sure of that. Apparently his father was given to rages - who can blame him.

Bernhard Berenson came into his own in Boston with attendance at Harvard, his crowning glory. It must be said of course that neither Boston nor Harvard welcomed Jews. And the German Jews who had already established themselves in Boston did not greet their Eastern European and Russian brethren with any enthusiasm. And yet Berenson prevailed. Beginning at the Boston Public Library where his voracious appetite for books, all kinds of books on all sorts of subjects began and then Harvard, where his tuition was paid for by Edward Warren, the first of several wealthy Americans who made possible what otherwise would have been beyond his reach.

Berenson wanted to fit in, of course he did. His father’s family had changed its name in such a bid. Berenson went still further, he changed his religion. But passing over is tricky and never really complete. Assimilation is a journey; it is a goal never reached. Being baptized in the name of Christ did not make him a Christian. He did not shed his old skin, he was not reborn. By the age of 20, the piling on of what he tried to hide from others but somehow never really could, was an integral part of him, as it was, as it is. for so many still.

His intellect at Harvard was often acknowledged but not always appreciated. He took art history courses taught by Charles Elliot Norton, Harvard’s first professor of art history. Those courses changed Berenson’s life but that wasn’t Norton’s intention. Art history, Norton contended, (and he was not alone) was not a discipline for the “pushing immigrant classes”. Norton told a colleague that Berenson ‘ha(d) more ambition than ability,’ a comment repeated. A comment that haunted Berenson for the rest of his life.

Berenson applied for a Harvard traveling fellowship his senior year, endorsed enthusiastically by all his professors, save one, Norton. Without Norton’s support, Berenson did not win the fellowship.That was a disappointment money could fix and money was found. A group of benefactors, among them, Isabella Stewart Gardner, funded Berenson’s year of European study. It was a pattern Berenson was to maintain, when institutional prejudice kept him from gaining university or museum posts, patronage paved the way. There is nothing wrong with patronage, of course. Patronage was how the Renaissance artists whose work and lives Berenson would become expert in, had flourished. Michelangelo, as we know, spent his growing up years in the Medici household, surrounded by classical art and classically trained humanists. Mantegna received a stipend from the Duke of Mantua and like Leonardo in Milan and later in France, was called upon to paint frescoes as well as create table decorations for weddings and Easters. The idea of artists painting what pleased them and what they hoped would please a wealthy buyer, did not appear until the 17th century and initially in Northern Europe. Until then, artists were dependent upon the Church and wealthy private patrons for commissions. Patronage enabled Berenson to survive, too.

Berenson's European travels were extensive. His one year abroad became a seven year wanderjahre. Do you know that term? It dates from the middle ages and it refers to the years of travel that craftsmen took after their apprenticeships. Painters, sculptors and architects traveled after their apprenticeships, too. Styles and techniques were diffused from one region to another that way - think single point perspective traveling north and oil painting techniques traveling south. (Better to think of those than how Covid-19 spread around the world). Berenson had already spent time in England before he left for the Continent. He had already visited Belgium, Germany and Austria before he arrived in Venice in the fall of 1888.

He wrote to Mary Costelloe, the woman who would become his wife, “When I …. had my first look at the Campanile and S. Marco I thought they would fall on me, I have read since that blind people suddenly restored to sight feel just so about their first glimpses of the world”.

Berenson’s reaction to Venice was not unlike Benjamin West’s reaction to Rome. West, as you probably know, was the first American born artist to achieve European acclaim. Like Berenson, West’s European voyage (in 1760) had been underwritten by local benefactors. (as an aside, Alexander Hamilton’s 1772 voyage TO American, from the West Indies, was underwritten by benefactors) Like Berenson, West was overwhelmed by the beauty of an Italian city. West wrote (in the 3rd person), “(F)rom the cities of America, where he saw no.. .painting(s)…to the City of Rome the seat of art and taste, had so forcible an impression on his feeling that he was under the necessity of leaving …'

What the 18th century artist and 19th century aesthete suffered were the symptoms of ‘Stendahl’s Syndrome,’ a ‘psychosomatic disorder that causes rapid heartbeat, dizziness, fainting, and confusion when an individual is exposed to an experience of great personal significance, particularly when viewing art’. Stendhal described it this way, “ I was in a sort of ecstasy, from the idea of being in Florence.… Absorbed in the contemplation of sublime beauty.… I had palpitations of the heart.… Life was drained from me. I walked with the fear of falling”.

Unless one tumbles into the street and is run over by a moto, or a Fiat or a bus, the disorder is fatiguing but not fatal and one can gradually begin looking at the gorgeousness that is Italy without fear of losing consciousness. After Venice, Berenson traveled to Florence, where he spent the winter and spring (1888/89) as he would nearly every year for the next 61.

Berenson left Boston anticipating a literary career. But all that changed when he got to Italy. It was the study of paintings that seduced him then and became the centerpiece of his long and productive life and career. It wasn’t really the intellectual underpinning of Italian art that attracted Berenson when he got to Italy. It was connoisseurship. And it is easy to understand why. The art history classes Charles Elliot Norton taught at Harvard were without images, without photos. When Berenson got to Italy, paintings were everywhere, churches were filled with them, palazzi were, too. And when Berenson arrived in Italy, two Italian art historians, Giovanni Morelli and Giovanni Cavalcaselle were just then formulating a systematic means by which to establish an artist’s oeuvre, that is, to determine who painted what. Which paintings could, for example, be attributed to Botticelli, which works were probably by a pupil, which by a follower and which by a forger. Morelli contended that every artist has a particular way, a signature way, of painting unimportant details. And it is those details which are consistent within an artist’s work. So, for example, while a forger would painstakingly work to master the signature of the artist whose work he was copying, when it came to painting something like the folds of an earlobe, he would paint it in his own way. That would be the evidence to use to distinguish a Botticelli from a ‘looks a lot like a Botticelli’. One art historian writing of Morelli’s methods, has compared them to those used by a detective. Think Sherlock Holmes who could gather evidence from observing seemingly insignificant details - the mud on somebody’s boots or the tobacco stain on somebody’s index finger.

Berenson brought with him to Florence a letter of introduction to Paul Richter, a connoisseur who used Morelli’s methods to study paintings by Leonardo. Richter was also a dealer, receiving a percentage of the price of a painting from whomever owned it when he found a buyer for it. This was Berenson's ‘aha’ moment. With his encyclopedic visual memory and his capacity to see, to really see, Berenson had found in connoisseurship, the possibility of a career.

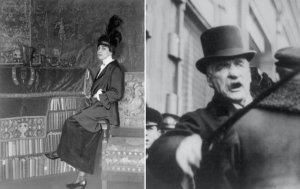

When we left Bernard Berenson, it was 1887. (Figure 1) He was a recent graduate of Harvard University embarking upon a voyage to Europe. The university travel grant he had hoped to receive hadn’t materialized. But private patrons, among them Isabella Stewart Gardner, who, with Berenson’s assistance, would eventually own one of the finest collections of Italian Renaissance art in the United States, paid for his trip. This trip to Europe, followed by only 12 years his first trip across the Atlantic. That voyage had been in the opposite direction, when he and his family emigrated from Lithuania to Boston. In a little more than a decade, Berenson had already traveled quite a distance - from impoverished immigrant to accomplished alumnus of America’s premier university.

Figure 1. Bernard Berenson at 21

He had planned to stay in Europe for one year, but that one year eventually stretched into seven. Early on, he visited England where he fell under the spell of Walter Pater, the original “art for art’s sake” guy whose writings on Italian Renaissance art simultaneously celebrated the individual artist-genius and the right of individuals (such as himself, such as Berenson) to respond idiosyncratically to those works of art. As an aside, that is why doctoral programs in the humanities exist, that is why tenure is to mostly based on publishing articles and books. Because if there was only one way to understand works of literature, of art, of historical events, then one description/discussion would be sufficient. But different generations, different groups (marxist, feminist, queer, etc.) interpret the past through a lens that is particular to themselves, to their time, to their place and to their way of interpreting the past, understanding the present. So, there is no single interpretation of historical events, of Shakespeare’s sonnets, of Michelangelo’s sculptures.

Berenson visited Paris and Northern Europe before traveling to Italy. It was in Italy that he found his groove, at the age of 24, two years into his seven year wanderjahren. Berenson met Giovanni Morelli in Rome and became an adherent of Morelli’s technique of determining who painted what. Berenson decided that rather than become a writer, as he had planned, he would become a connoisseur of Italian Medieval and Renaissance Painting. The task confronting him must have seemed both daunting and delightful. A cheese connoisseur has to eat a lot of cheese, a wine connoisseur has to drink a lot of wine. A painting connoisseur has to see a lot of paintings. And so Berenson embarked upon what was to be the journey of his career, of his life. He visited museums, of course (the Uffizi opened as a museum in 1865,the year of Berenson’s birth) but mostly he visited churches and palazzi, where so many of the paintings resided, at least until he and his clients got to them.

One reviewer has suggested that Rachel Cohen’s biography is organized around the women in Berenson’s life. And it is true that women take center stage here. He had so many female friends and lovers and so many of them overlapped, I mean in his life, not, I don’t think, well, I don’t really know, in his bed, that it seems just the right organizational scheme. These women were talented and interesting and enhanced Berenson’s life quite as much as he enhanced theirs. Berenson may have been, at one point in his youth, attracted to men, but with so many other aspects of his life to hide (or try to hide): race, religion, roots; trying to hide an aberrant (at the time) sexual orientation would have been just too stressful, don’t you think ? Berenson knew Oscar Wilde and the cautionary tale that was, eventually, Wilde’s life, would have confirmed Berenson’s view that sexual attraction to or love for another man would have been too dangerous a choice. Berenson didn't stop trying to change who he was, though. He converted to Catholicism, which he said seemed like the right thing to do in Italy. And after the First World War, he dropped the ‘h’ in his first name, going from Bernhard to Bernard, making it less German and more French, again because it seemed like the right thing to do at the time.

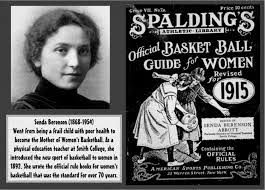

The first woman who had an impact on the adult Berenson was his sister Senda, three years his junior. (Figure 2) And her trajectory confirms that Berenson’s family was an exceptional one. When Berenson stayed longer than the anticipated year in Europe, Senda sent him small sums of money as she could, even returning to her parent’s home so she could continue to fund her brother’s travels. Senda was a frail young woman and physical pain forced her to forego formal education. She eventually took her health in hand through physical education training. With neither high school nor college degrees, she joined the faculty of Smith College as a physical education teacher. Further, she introduced the new game of basketball to women’s sports. Celebrated as the ‘Mother of Women’s Basketball,’ she wrote the Basketball Guide for Women and in 1985, was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame. Do you remember playing basketball in high school, I do. Girls didn’t play full court basketball like our brothers and boyfriends did. No, we played something called basket and ball, staying in and then rotating among three positions, shooter, passer and blocker, remember? Cooperation in women’s sports was Senda’s goal for her young female charges. Cooperation not competition.

Figure 2. Senda Berenson

One summer Senda visited Berenson in Italy but it did not go well because her brother was involved with a married woman. That woman, Mary Costelloe who was also from Boston, met Berenson in London where she was living with her husband, a banker, and their two daughters. (Figure 3) Mary, an unconventional woman before Berenson entered her life, threw convention further to the wind when she abandoned her husband and children to study art and make a life with Berenson. His achievements were to a very large extent, their achievements and he never hesitated to give her credit. Hers was the more organized mind and her lists kept track of what they had seen where and what his/their thoughts had been about what they had seen. She was an art historian, as the phrase goes, ‘in her own right'. She was slated to be listed as the co-author of his first book on Venetian artists (1894) but her mother, a feminist, dissuaded her, worried that her daughter’s reputation would be sullied. Bernard and Mary had become lovers in 1890. She moved to Italy to be with him 1892, but until her husband’s death 7 years later, they had separate lodgings to avoid scandal.

Figure 3. Mary & Bernard Berenson at Villa I Tatti

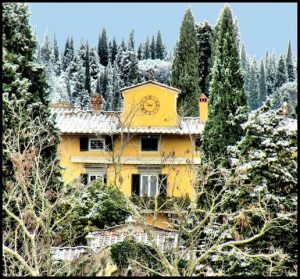

In 1900, the Berensons moved to the Villa I Tatti, in the hills above Settignano. (Figure 4) Initially they rented the villa but when the owner, a local English expatriate, died, they bought it from his heir. Their lives in Italy read a lot like the bohemian lives of the Bloomsbury group and many members of that group wandered in and out of I Tatti over the years. It is reassuring to know that Mary was as unfaithful to their marriage vows as Bernard was. I will tell you about two lovers that Rachel Cohen mentions, one of them Mary’s, the other, Bernard’s. Snarky and indiscreet are the two adjectives that comes most readily to mind. Here is Mary’s story. After they bought I Tatti, Mary hired two young English architects to renovate, repair and expand it. One of the young men Mary hired was Geoffrey Scott with whom Mary was in love. The Bloomsbury biographer and critic Lytton Strachey explained the relationship this way to a friend, that although Mary “was frantically in love with (Scott). He remains a confirmed sodomite, and she covers him with fur coats, editions of rare books, and even bank notes and all of which he accepts without a word and without an erection.” That my friends is snarky, of Strachey to write of Cohen to quote and of me to repeat, hashtag sorry not sorry.

Figure 4. Villa I Tatti, Settignano, Italy

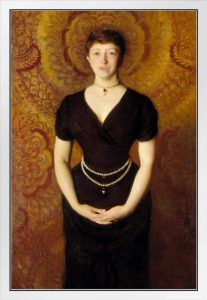

Two other women, significant to Berenson, were not sexual partners. One was Isabelle Stewart Gardner who appeared early and then often in Berenson’s life. (Figure 5) She was one of his first benefactors and was among his first clients. Indeed, she built her collection of Italian Renaissance art with his guidance. Sometimes he would find paintings for her collection himself and negotiate with the painting’s owners, more often he negotiated with a dealer. In both instances, he would retain for himself a percentage of the sale price. This was how Berenson was able to live independently in Italy, to make a life for himself and begin to send money home to his family in America.

Figure 5. Isabelle Stewart Gardner by John Singer Sargent, 1888

Berenson’s other significant friendship with a woman not his lover was with Edith Wharton. (Figure 6) They became friends in 1909 and remained so until her death nearly 30 years later. They visited each other often, traveled together frequently, and when apart, they wrote constantly. Her affection for Berenson notwithstanding, anti-Semitic comments popped up with some frequency in her correspondence as did unflattering descriptions of Jews in her books.

Figure 6. Bernard Berenson & Edith Wharton

I will mention two other women in Berenson’s life, both lovers. The first was Belle Da Costa Greene, J.P. Morgan’s librarian. (Figure 7) To explain her dark complexion, Bella Greene said she was Portuguese. We know now that was a lie - she wasn’t Portuguese, she was black. Indeed, her father was the first black graduate of Harvard and a prominent lawyer. Her parent's marriage foundered when her mother wanted the family to pass for white, which Bella, her siblings and her mother eventually did, once her parents separated. The love affair between Bella and Berenson was a passionate one and Bernard accompanied Bella on buying expeditions since her boss, J.P. Morgan, gave her complete freedom to purchase whatever books and manuscripts she wished to build his library. Here is the indiscreet part. Cohen speculates that Bella was a virgin when she met Berenson. Bella’s biographer thinks that she became pregnant on one of their buying trips and had an abortion in England. Obviously, Bella couldn’t have had a child, It is difficult enough these days to be a single working mother, it would have been financially and socially impossible then. And what would she have done, how would she have explained it, if the child was born darker than she? Just think back to all the speculation that surrounded the birth of Archie, the son of Prince Harry and Meghan Markel. I don’t think that Bella ever told Berenson that she was black. He was a married man when she met him. A married man who had had many lovers before her. Revenge porn is a thing now, with jilted or spiteful lovers sharing intimate photos of their former partners on the internet. Even without the internet, she would have had too much to lose if she had confided in him.

Figure 7. Bella Da Costa Greene and her boss, J.P. Morgan

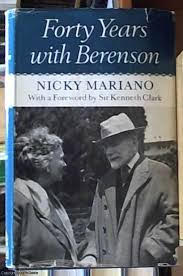

Finally, there is Nicky Mariano, (Figure 8) the woman who became a member of the Berenson household in 1919 and remained until Bernard’s death in 1959 and indeed beyond, overseeing the transition of the Berenson’s home of nearly 60 years into the Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies. Nicky was invited to I Tatti by Mary to become their librarian. She eventually became the beloved third person in a very tight triad. She traveled with the Berensons and when Mary initially was too tired and eventually too ill to travel, Nicky took her place and traveled alone with Bernard. When the Nazis came calling, she hid with Bernard for more than 18 months at a friend’s home. Mary was too ill to move and too indiscreet to be told where they were. Nicky was exactly the right person at the right time to make order out of what had become the chaos of the Berensons’ life as age and illness tore them apart.

Figure 8. Nicky Mariano & Bernard Berenson

So what exactly did Bernard Berenson do that enabled him to acquire and restore a medieval Tuscan villa for which he amassed an impressive art collection and a significant library. How was he able to travel so extensively and live so lavishly for so many years. We know that Bernard Berenson was a connoisseur. But, where, I hear you asking, is the money in that? Well, beginning with the methodology devised by Giovanni Morelli, he honed his ability to attribute paintings to the artists who painted them. Although Charles Eliot Norton, Berenson’s Harvard professor and nemesis, disparaged Morelli’s technique as the ‘ear and toenail’ school; before microscopes, spectroscopes, x-rays, and the rest, Morelli’s methods offered a start. For a scientific study to be considered valid, other scientists must be able to replicate it. For an attribution to be valid, it has to depend upon more than intuition and sentiment. Morelli’s method brought a sort of scientific approach to the attribution of paintings which had not been the case prior to Morelli and Berenson. Please don’t tell me that many of Berenson’s attributions have subsequently been questioned or changed, I know. That’s what happens when new information comes to light and improved techniques are discovered.

Berenson had an encyclopedic memory and he took or dictated notes to Mary and then to Nicky when he was ‘communing’ with a painting, so he would remember every nuanced detail. He requested photographs of paintings he wasn’t able to visit, a collection which eventually numbered in the thousands. And as rail travel became easier, he was able to see more and more paintings in situ. When Berenson first began authenticating Italian Renaissance painting, they were mostly purchased by English and European collectors. But soon, American collectors got into the game and Berenson was ready for them.

I read a paper once by an art historian about Robber Barons (Figure 9) and their art buying habits. The writer (an art historian) showed (with graphs and charts, not paintings!!) that when these men were taking risks in business, they were making conservative art buying decisions. When they were making conservative business decisions, they took risks with the art they bought. What would constitute ‘safe art’? Well, obviously, art by living artists, which didn’t need to be authenticated. That tactic wasn’t without its pitfalls of course. There were dealers, like the Baltimorean we discussed some months ago, who simply bought the wrong art, art that is now consigned to museum storage or worse.

Figure 9. American Robber Baron (money bags head with poire face reference)

Collectors also purchased old master paintings. And of course, they wanted to be sure that what they were buying was the real deal. If a painting hadn’t been hanging in the same palazzo or church for the previous 400 years, then it needed to be authenticated by experts.

Those Robber Barons, who fancied themselves descendants of the Medici and other Renaissance banking dynasties, were masters of wheeling and dealing in their professional lives but they expected the connoisseur who authenticated the paintings they were considering to be as pure as the driven snow. They expected that the authenticator would have no financial incentive when making his attribution. Berenson was scrupulous about his authentications and refused to succumb to pressure to attribute a painting if he wasn’t at least 100% sure of his attribution. But the fact was that his consultation fees with the Dutch Jewish (Jewish Dutch?) art dealer, Joseph Duveen and the percentage of the sale price he received when a painting he authenticated, was sold, permitted his grand and glorious lifestyle. He tried to keep his contract with Duveen secret because he didn’t want to be accused of exactly what people accused him of - attributing paintings to increase their price and therefore his payout. Berenson’s attempts at secrecy only added to the toxic brew of anti-semitism and whispers about a poor man who got too rich.

Ironically, Berenson tried and failed repeatedly to go legit, to become a university professor or museum curator but institutional prejudice thwarted his efforts. And really, how could he have ever imagined that he could afford to be a professor or a curator? You have to already be rich to accept one of those jobs or be content with genteel poverty if you are not. In the end, Berenson could not escape his Jewish heritage, he was in the ‘trades’ as they say in England, and that’s not a compliment.

Ironically, the first Jewish professor of art history at Harvard was Paul Sachs, whose personal wealth came from his family’s investment firm, Goldman Sachs. He could have worked at Harvard for free. And it was Sachs with whom Berenson organized his gift of I Tatti to Harvard. As Rachel Cohen writes, “It was evidently a matter of peculiar importance to Berenson that Harvard, which had made it possible for him to be a connoisseur and, in some ways, had prevented him from being anything else, should now accept (I Tatti) as a gift,…”

Here are a few things I am thinking about. The fabulously wealthy men who bought Italian Renaissance paintings from art dealers like Duveen, paintings which had been authenticated by connoisseurs like Berenson, eventually donated their collections to American museums like the Met and the National Gallery, or established collections in their gorgeous mansions which are open to the public, like the Isabelle Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston and the Frick in New York. (Figure 10) And while I am delighted that these paintings are available for all of us to enjoy, every so often I ask myself if those industrialists couldn’t have made a little less money by paying their employees a little more money, say, for example, a living wage? These industrialists amassed their fortunes at a time when there was no minimum wage or maximum work week, why couldn’t they have been more reasonable as employers ? These men had not inherited their money, they were nouveau riche, they were arrivistes. They were buying their way to respectability, so why did they begrudge Berenson the same?

Figure 10. Frick Collection, New York City

And if it was anyone’s fault that Italian Renaissance paintings were so expensive, it was their own. The answer to how much a painting is worth, is how much someone is willing to pay for it. As the art critic who wrote about the David Hockney painting that sold for $92 million said, a painting’s value is anywhere between priceless and worthless.

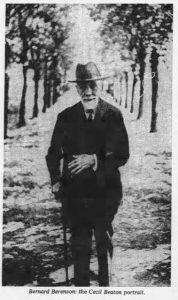

Finally, as Rachel Cohen notes, Bernard Berenson made “foundational contributions to art history, art criticism, and the collecting of art in the United States” and yet his life was constrained by prejudice. Berenson admonished his fellow Jews, quoting Heinrich Heine, “In order to be taken as silver you must be of gold.” (Figure 11) And isn’t this the same lament that all races, religions and genders that aren’t straight, white, male and pedigreed, confront when trying to climb the ladder of success, indeed when trying to survive. This is a great book. You really must read it.

Figure 11. Bernard Berenson by Cecil Beaton

6 comments

Jacquelyn Goudeau7 January 6, 2021

Passing for anyone other than who you really are-is tricky, Dr.B. either UP DOWN OR SIDEWAYS. FIGURING OUT WHO we really are-takes heart more than head? Bonne Annee Jacquelyn Goudeau

Francis Meltzer January 12, 2021

Since you asked me « when not if...» plural of nouveau riche is nouveaux riches. Wishing you a happy and brilliant year, JFM

Shirley Lerman January 12, 2021

Thanks you so much for that wonderful, informative review.

Deedee Remenick January 12, 2021

Another fabulous comprehensive "lecture" . Makes being in lock down bearable.

Jacquelyn Goudeau January 13, 2021

Did not know about Berenson Thanks for the input. Bella de Costa Greene-passe blanc- quite usual for the times.Sadly understandable. Merci JG

Julia Frey January 21, 2021

Dr. Beverly's absolutely best article. I knew very little about Berenson, and she made it a delightful lerning process. I loved it