TG: How long has the idea for your Café French book been percolating in your mind?

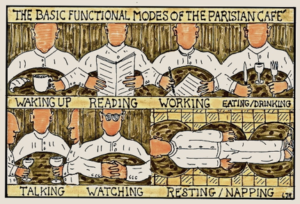

LJH: I started to write about my love of Paris cafés after my Foodoodles book came out in 2010. Based on that cartoon memoire about my foodie life in Berkeley, I was invited to write for an online food journal called Zester Daily. I told them that I wanted to write and illustrate a series of articles on Paris cafés and they said yes, though my offbeat material was hardly the standard fare of food journalism. That was the birth of ten so-called “Café French Lessons” and I was very grateful to Zester for letting me wing it. The conceit was that I was giving French lessons ("café French") to my readers to help them hang out in Parisian cafés and communicate with les garçons and Paris locals. Of course that was a huge joke because I was learning the very French I was "teaching." The challenge was to come up with a pictorial style to illustrate the new vocabulary (faux amis, jeu de mots, etc.) I was discovering. I think I succeeded to the extent that the drawings do advance the linguistic material and provide a jumping off point for my narrative meanderings.

TG: Your subtitle contains the word “flâneur”. What is a flâneur?

LJH: The flâneur is an urban type who inhabited Paris in the 19th century--and earlier-- as a strolling observer—the verb flâner means to stroll. Balzac called flânerie "the gastronomy of the eye." Charles Baudelaire was considered the quintessential flâneur by the German critic and philosopher, Walter Benjamin. Baudelaire wrote many of his poems based on what he encountered while strolling the streets of Paris, often at night. The Surrealists continued this observational strolling activity into the 20th century. Perhaps the flâneur emerges out of the earlier boulevardier, the difference being that the boulevardier was an extrovert who wanted to be noticed. The flâneur dressed as a bourgeois and wanted to remain incognito, to observe unobserved. The new field of journalism was developed by observing flâneurs.

TG: To paraphrase Sam Clemens apropos of the French Café: “Rumors of my demise have been exaggerated.” What is the role of the café in quotidian Parisian life and is it alive and well or threatened by Starbucks?

LJH: The French café is certainly threatened today, and not just by Starbucks and its ilk. There are all kinds of scary statistics on the declining numbers of traditional cafés caused in part by neighborhood gentrification and changing French lifestyles and attitudes towards work. But Clemens was right and today tourists provide a much-needed boost to French cafe culture because they are willing to pay high prices to absorb the historical vibe, like paying to go to museums. Organizations like Save The Paris Cafe headed by Lisa Anselmo are promoting the benefits of traditional café culture and even the French government is addressing the problem. Perhaps the real threat to Paris café culture is that young Parisians, as in America, go to cafés not to experience la vie en rose, but to work! Hence the emergence of "le co-working café" where you pay by the hour to sit and stare at your computer.

TG: What can you expect to find on the menu at a café?

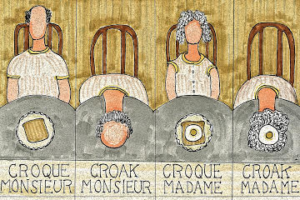

LJH: Café menus are pretty formulaic. They feature many of the classics of regional French cooking like quiche Lorraine, boeuf Bourguignon and Brittany crepes. And then there is the lighter fare like paté and cheese served with baguettes, and of course croissants and brioche with coffee in the morning. The toasted ham and cheese sandwich, croque monsieur is ubiquitous, launched in cafés about 100 years ago. But no one goes to cafés for high-level gastronomic experiences. Cafés satisfy hunger--for nourishment, sociability, creative solitude and flâneurian observation enhanced by caffeine or other stimulants (wine, absinthe, etc.). I give a pretty bleak view of the quality of Paris’ café food in Café French and devote two chapters to the croque monsieur and roast chicken, both of which should be better than they usually are.

TG: What is your favorite café or cafés? And why?

LJH: I go to Deux Magots every year to celebrate my arrival in Paris. A glass of champagne in front of Eglise Saint Germain really brings home that I have arrived somewhere very special. Maybe it’s accentuated by jet lag, but I feel euphoric when I’m there that first day or night in Paris. I particularly love the hourly bells that ring out from the medieval church, a sonic immersion in history. I go to Café Flore down the street on a more every-day basis. It seems less pretentious than Magots but still has historic literary vibe. Cafe Select in Montparnasse has plenty of vibe and pretty good food. La Palette is in the heart of the Latin Quarter gallery scene. It’s chic and snooty with decent food. Shakespeare & Company has their own cafe now with coffee that rises above the level of most Paris cafés. I like Café Madame on rue Madame in the 6th because it’s more a neighborhood café than a tourist café. Nearby is Café Fleurus, again a local scene.

TG: Speaking of which, what is the state of coffee in Paris? Have you found alternatives to the ubiquitous RICHARD FRERES, the Auvergne “mafia?” I use the word advisedly--I don’t think they are breaking legs but they do monopolize the supply chain from coffee to tableware.

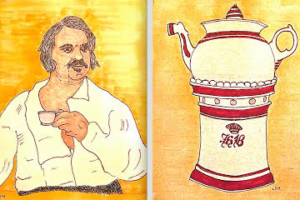

LJH: There has been a lot of attention paid to the poor coffee in Paris. I’m not really the right person to ask about this because I tend to forgive the bad coffee if I’m excited by the setting and/or the history of a café. And I’m not going to go to the co-working cafés just to have a better level of coffee. Cafés are not really about the coffee anyway. Like for Balzac, it’s the chemical buzz that counts, not so much the taste. My chapter on Balzac goes into some detail about his addiction to coffee and its role in creativity. FYI: When I get a really bad café creme in Paris I have technique for turning “water into wine.” I take the little chocolate square served at many Cafés Richard cafés and put it in the coffee to melt it. Then I add sugar, stir and voila! It’s a sweet café mocha that buffers the harsh flavor of commercial Robusta beans.

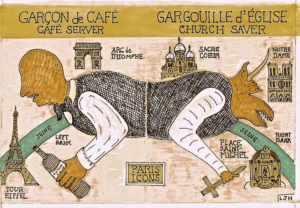

TG: No discussion of French cafés would be complete without mentioning the "garcon.” Your thoughts and observations please.

LJH: It's hard to imagine the café and its "culture" without the garçon and his culture: efficient, sometimes abrasive edging on rude, knowledgeable, and totally in control. In Café French I describe him as combining the efficiency of a butler and the arrogance of a dandy. Unlike the American waiter, he is not working for tips.

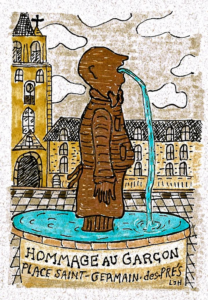

He is a paid professional and demands the respect that deserves. The attempts of a few years back by the Paris tourism authorities to make the garçon "nicer" was a joke, though maybe it worked because I found the servers at my regular cafés this summer pretty friendly. Maybe they recognized me after so many years coming to Paris. I even showed the manager at Deux Magots my drawing from Café French of a proposed garçon fountain to be installed in the plaza between Magots and the St. Germain church as an homage to this important cultural type and he loved the concept! Fat chance that an American can make this happen, but I'll present it next summer to the local authorities.

TG: And finally, how do you incorporate French café life into your Berkeley routine?

LJH: It’s a struggle, really. The last chapter of Café French describes the depression I experience when returning to Berkeley from Paris. There is no real sidewalk café culture at home. Paris flâneur morphs into Berkeley foodie. There is no urban splendor on the level of Paris, not even in San Francisco. So I improvise. My village life in Berkeley (North Berkeley’s so-called Gourmet Ghetto) has its own rewards which reveal themselves after about a month or so back home. The coffee is great, as is the food, but the Parisian café vibe is missing. My need for the buzz of a morning café finds it at our very fine Jewish deli, Saul’s. There is a long tradition of European Jews coming to the East Coast and turning Jewish cafeterias, restaurants and delis into an expat café culture. In the afternoons I take my journal or a book I am reading, or a draft of something I’m writing, to Masse’s French pastry shop next to Saul’s. They have great coffee and good financiers and madelaines and I sit and plot my next trip to Paris. Vive la différence!

TG: See you soon!

LJH: Oui, à bientôt.

John's book is available at bookstores, Amazon and in Paris at Shakespeare & Co. and The Red Wheelbarrow