Victor Brauner at MAM (Musée d’Art Modern de Paris)

Beverly Held, Ph.D. aka Dr. B.

Figure 1. Victor Brauner Je suis le rêve. Je suis l’inspiration. Exhibition Poster, MAM

I wasn’t completely honest with you last week when I told you that the last exhibition I saw before everything closed down again in Paris was the Sarah Moon exhibition at MAM (Musée d’Art Modern de Paris). There was another exhibition that I saw, also at MAM, also only hours before reconfinement which will (eventually) be the subject of this review. Indeed, I could have gone to a third exhibition at MAM but Dear Reader, I went to CityPharma instead and really did risk my life fighting my way along packed aisles to buy beauty and health products for insanely low prices. As a girl (now woman) who has had one abiding mantra over the years, that being ‘Never Buy Retail,’ CityPharma is a dream come true. And if you don’t know about this pharmacy, I am surprised because it is on Rue du Four, just down from that crazy statue of the Centaur who, it must be said, is a marvel to observe from behind. (Figure 2) This centaur, as with most representations of such beasts, has the hind quarters of a horse and the torso and head of a man. In this case, the head is a self portrait of the sculptor, César. Baldaccini (who also btw sculpted the French equivalent of the Oscar, and gave his name to the award) Of interest to us, of course, is that on its breastplate is a miniature replica of the Statue of Liberty. (Figure 3) Rest assured, I bought enough vitamins and Caudalie produits at CityPharma to justify the risk and hopefully last until deconfinement.

Figure 2. Centaur, César Baldaccini, 1983

Figure 3. Centaur, breastplate detail, Statue of Liberty. César Baldaccini, 1983

Right, the exhibition. Well, the subject for this exhibition is Victor Brauner. He was a pretty (very) weird guy. Synchronicities? You bet. Do you remember the exhibition I wrote about very soon after the museums started opening up again in June ? Called ‘Esprit es tu la?’ (Spirit are you there?) Brauner’s connection to Spiritualism started young and lasted a lifetime. Do you remember the portrait that Giorgio de Chirico painted of Apollinaire, with a mark on the forehead which anticipated the wound Apollinaire was to receive some years later during WWI? Brauner did him one better as we shall see (the word ‘see’ foretells). Like Felix Feneon about whom I wrote sometime ago, Brauner collected the arts of Oceania and Central and North America. Unlike Feneon, who was a collector, Brauner, as an artist, incorporated the art of distant lands (to quote Albrecht Durer) into his own work. Do you remember the review of the sculptor Zadkine whose studio/museum is on rue d’Assas. As a Jew, he fled Paris for New York during the Nazi occupation of Paris. His long suffering wife, Valentine Prax didn’t go with him. Instead, she headed south, to their little country cottage. Brauner was Jewish, so he had to leave Paris too, but his visa for New York never came through. He went into hiding in the countryside. Both Prax and Brauner suffered immeasurable privations during the war. Afterwards each said that the time spent in isolation and privation had been their most productive times as artists. Isolation minus the privation should be easier to bear, right?

Victor Brauner was born in Romania in 1903. His father, a timber manufacturer (bought trees, sold lumber?) was described by Victor’s brother as a ‘poet, socialist and theosopher.’ We talked about Theosophy and the usual cast of characters - Madame Blavatsky, Rudolph Steiner and the artist Vassily Kandinsky - when we discussed the ‘Esprit es tu la?’ exhibition. Briefly, Theosophy is a belief system which contends that contact with a deeper spiritual reality is possible through intuition, meditation, revelation and/or some other state transcending normal human consciousness. I don’t know if that is intended to mean drugs, but since I am from San Francisco, I am going to go with yes on that.

Brauner’s father was a passionate devotée of spiritualism, magnetism, and hypnotism. He organized sessions with mediums to communicate with spirits in the beyond. Halley’s Comet was scheduled to appear on May 18, 1910. Brauner’s father anticipated the end of the world. That’s interesting, when the comet appeared before the Battle of Hastings in 1066, it was perceived as a harbinger of good tidings. Well, for William the Conqueror it was, because he won. For Harold, not so much since he was killed in battle. He is depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry (embroidery) lying on the ground with an arrow in his eye (note to self, remember the eye). Brauner’s parents dressed their 7 year old son in his Sunday best so he could attend the end of the world appropriately attired.

Here’s my question, if you consider Halley’s Comet as a harbinger of the end of the world, and you wake up the next morning, shouldn’t you reconsider the set of beliefs that led you along that path? Well, apparently not for Brauner père nor for Brauner fils, since he was to add other ‘other worldly’ world views to his repertoire of beliefs over the years. As we will see, these included Tarot and the Kabbalah.

After getting kicked out of art school for being an anti-figural non-conformist, he made his first trip to Paris (1925) where he was introduced to Surrealism. He traveled between Paris and Bucharest for much of the 1930s. Finally, because of the deteriorating political situation in Romania, specifically the fascism, the anti-Semitism, and the increasingly difficult art scene, Brauner fled Rumania and settled in France permanently in 1938.

Brauner read a great deal in psychoanalysis; and according to Saul Steinberg, who was also born in Rumania and who knew Brauner in Paris, Brauner had an intense interest in extra-sensory perception. Of course he did, he was brought up with it. But there are in Brauner's own biography several incidents that anticipate the future. For example, in 1931, he painted one of his most well-known works - a self portrait with one eye enucleated. (Figure 4) Although he was never able to explain what prompted him to paint that self portrait, he may have seen, as you surely have, the 1929 surrealist short film by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, Un Chien Andelou. I am talking about the creepy scene of a young woman’s eye being sliced with a razor.

Figure 4.Victor Brauner Self-portrait, 1931

(Figure 5) That was the only image I could muster when I anticipated my cataract surgery. And it probably wasn’t that far from the truth, as I experienced it, here in Paris, with local anesthetic.

Figure 5. Un Chien Andelou, Luis Buñuel & Salvador Dali, 1929

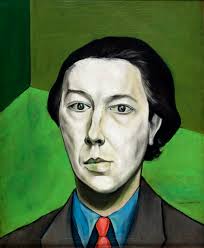

When Brauner met André Breton, the father of Surrealism, he happily joined the group. Alas connecting with Breton meant breaking with his countryman Constantin Brancusi (with whom he had been hanging out) since Brancusi wanted nothing to do with Breton’s authoritarianism. Question, how is it possible that somebody who celebrates the unconscious and chance is such a dictator? I’m talking to you, bossy pants, André Breton ! (Figure 6)

Figure 6. Portrait of André Breton, Victor Brauner, 1934

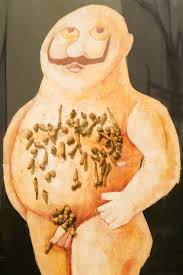

In 1934, Brauner exhibited 17 canvases entitled, ‘The Strange Case of Mr. K.’ Brauner conceived the figure, Mr. K. as the embodiment of a ridiculous stupid fascist politician. Gosh that sounds awfully contemporary, but it is actually a reference to Alfred Jarry’s play, Ubu Roi a satire on power and greed, particularly the complacency of the bourgeoisie who abuse authority to acquire riches. Brauner’s grotesque version of Ubu, shows the king, Mr. K. naked and obese, his body covered with tiny celluloid dolls. (Figure 7) Some viewed Mr. K. as a universal image of overwhelming authority. André Breton saw another angle, an example of the artist's struggle against 'all the powers of human enslavement'. Except of course the enslavement of others to a cause you control and to which you expect obedience, hmm.

Figure 7.The Strange Case of Mr. K. Victor Brauner, 1934

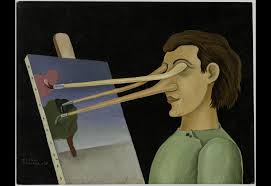

For the Surrealist Exhibition in 1938, Brauner produced the Loup-Table, (Figure 8) a hybrid of a table and a fox. It has a fox head at one end and a fox tail at the other. Hanging below the table at the tail end, and just like Cesar’s Centaur statue off the rue de Cherche-Midi, we see a very well hung fox. That same year, for an edition of a 19th century French poet’s work, Brauner painted a portrait of a man in which horns with brushes protrude in place of the subject’s eyes. (Figure 9)

Figure 8. Loup Table, Victor Brauner, 1939

Figure 9. Painted from Nature, Victor Brauner, 1937

Finally, in 1938, seven years after his self-portrait with an enucleated eye, the prophecy came true. He found himself one evening in August, in the middle of a fight between two fellow artists. When a wine glass was smashed, the shards went flying. One shard flew into Brauner’s eye, the left eye, the same eye that he had represented as missing in his self portrait of 1931. As reality theatre goes, this sure beats Giorgio de Chirco’s portrait of Apollinaire. It is one thing to vaguely anticipate a wound another will suffer, quite another to prophesize something that will specifically happen to yourself. Brauner was heralded as the “seer” painter, as De Chirico has been nearly 25 years earlier, the embodiment of the theory of “objective chance” so dear to André Breton’s heart.

Some writers have noted other harbingers of this dramatic event. For example, Brauner's painting of a tiger has the large letter 'D,' the initial of Oscar Dominguez, the artist who threw the glass that broke into shreds that pierced the eye of Brauner. And here’s another, when Brauner first arrived in Paris he took a series of photos for Brancusi. One of the photos is of the house in which Brauner lost his eye 7 years later. I think both of those coincidences are pushing it and don’t achieve ‘objective chance’ status, since Brauner used other letters of the alphabet in other paintings and none of them alluded to anything that happened to him. And about that house, well, artists congregate and it isn’t that unusual that one of the houses he photographed might be significant down the road. And then of course, there is another premonition that Brauner had, that he would lose a hand, for which, in anticipation, he actually purchased an artificial wooden hand, au cas ou. Thank goodness that prophesy didn’t pan out and his body remained more or less intact for the rest of his life.

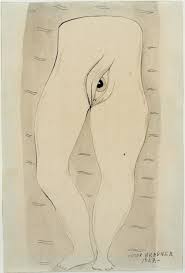

In the exhibition, in addition to that enucleated self portrait from 1931, Brauer depicted enucleated eyes in De Chiroco-esque deserted cityscapes and an all seeing eye nestling in a woman’s crotch (Figure 10). Have a look at his work, you’ll probably find other eye-xamples.

Figure 10. The Peaceful World, Victor Brauner, 1927

Brauner considered the loss of his eye as the defining event of his life. He wrote, “The hunter, to aim better, closes his left eye for a while. The soldier, the better to kill, closes his left eye. The player, in games of skill, closes his left eye the better to send the ball or arrow into the center of the target […] . I have forever closed my left eye; I was probably given by chance to see the center of life better” That’s as good a definition of making lemonade out of lemons as I have ever read.

It could be argued that the war that followed losing his eye had every bit as intense an impact on Brauer’s art, on his life. When the Nazis moved into Paris, Brauner fled to the south of France. But Brauner never got his hoped-for visa to the United States. He spent the entire war in hiding, always worried about being discovered - Jewish and Romanian, he had real reason to worry. He had almost nothing to make art with, so he made art with nothing, like voodoo dolls and ex-votos of pebbles and pieces of string; or paintings using a wax technique he invented himself, applied to a canvas or wooden support, colored with charcoal or walnut stain then scraped or incised - techniques he continued to develop and explore in Paris when he was finally able to return.

Brauner had always been a writer, incorporating words with images in his drawings and paintings. His isolation during the war enabled him to devote more time to writing, and his writings both document and explain his creative process. He also developed a new magical language, a ritornelle (a refrain which uses the same melody and the same words) of words and images. He was looking to discover a unity which would bring alchemy, Kabbalah and tarot together.

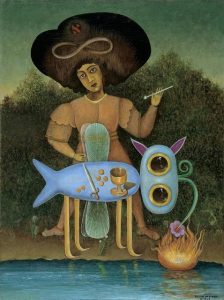

According to Elizabeth C. Childs, in The Surrealist, 1947, (Figure 11) Victor Brauner borrowed motifs from the tarot (a set of seventy-eight illustrated cards used in fortune telling) to create a portrait of himself as a young man. One tarot card, the Juggler, (Figure 12) provided Brauner with a key prototype: large hat and medieval costume. Both figures stand behind a table on which is a knife, a goblet, and coins. The tarot Juggler refers to the capacity of each individual to create his own personality through intelligence, wit, and initiative, to create his own future.

Figure 11. The Surrealist, Victor Brauner, 1947

Figure 12. Juggler, Tarot Card

In another tarot deck, the first card is the Magician. (Figure 13) The sign of infinity (the symbol of life) that appears above the Magician’s head also appears on the hat in Brauner’s painting. Using both the Juggler and Magician, Brauner illustrated the traditional signs of the four suits in the tarot deck: wands, cups, swords, and coins (symbols of the elements of natural life—fire, water, air, and earth, respectively). Like the Juggler who uses his wand, the Surrealist poet uses his pen and the Surrealist artist, his brush to create his own future.

Figure 13. Magician, Tarot Card

Brauner returned to Paris in 1945 and moved into the former workshop of Douanier Rousseau (1844-1910). Was it Surrealism or serendipity? Since one needs the other, probably both. Brauner continued to paint the creatures he had created during the war, especially his Conglomeros (contraction of conglomerate and Eros), a smooth, white, multi-limbed creature with enormous extraterrestrial heads, often a female body framed by two male bodies, all united in a single head with protruding eyes. (Figure 14) A painting by Douanier Rousseau, La Charmeuse de serpent (Figure 15) inspired Brauner’s La Rencontre du 2 bis, rue Perrel. (Figure 16)

Figure 14. Conglomeros, Victor Brauner, 1945

Figure 15, La Charmeuse de serpent, Douanier Rousseau, 1907

Figure 16. La Rencontre du 2 bis, rue Perrel, Victor Brauner, 1946

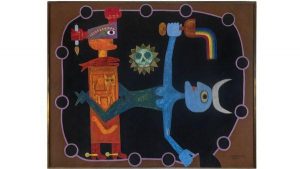

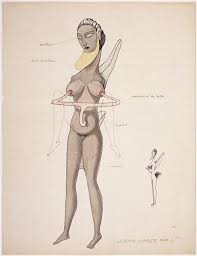

His postwar painting took forms and symbols from Egyptian hieroglyphics (beloved by the Spirit painters), Mexican bas-reliefs and colored totems of the American Indians. (Figure 17) Then there are some very weird, very kinky drawings of completely sexualized apparatuses that facilitate sexual congress without much social contact, (note to self, check this out). (Figure 18) As one critic wrote, Brauner’s work, like that of the other surrealists, “but in a more violent way, (uses) non-idealized eroticism as a formidable weapon against the hypocrisy of the social order.” How is enchaining a female body, every bit the victim of that social order, a weapon against it ? Never mind, I’ll never understand. This critic continued that the ‘raw eroticism’ in Brauner’s work “can arouse a certain reluctance of the spectators in front of this overflowing sexuality.” You think ? Well, my guess is that this is a guy who spent way too much time alone in the woods during the war and these were the thoughts that kept him going and since he was an artist, the drawings, that got him through what was surely a hellish period of fear and deprivation, on every level. That the kinkiness didn’t go away after the war, well, I’m not a psychoanalyst. His final series “Mythologies, is a little less hostile, although every bit as Freudian. For example his 1965 Autonoma, depicts a man suckling the breast of a woman, coiled in the body of a woman-car. (Figure 19)

Figure 17. Ceremonie, Victor Brauner, 1947

Figure 18. Complete Woman, Victor Brauner, 1936

Figure 19. Autonoma, Victor Brauner, 1965

Brauner’s work is an eclectic combination of belief systems and world views to which he gave visual form throughout his career; as one critic so perfectly described it, 'between the ocular and the occult, the esoteric and the erotic.’ From 1920, when he first started painting until 1966, the year of his death, he free flowed from dream to reality, from narrative to prophetic. Combining the spiritual, the primitive, the erotic, he created his own distinct style. He may not be as well known as other Surrealist artists, but his work definitely merits our attention. I know if things were different now, you would be happy to meet me at MAM to wander through the exhibition together, to count all the eyes and check out that fox.

3 comments

Julia Frey November 17, 2020

Thanks Dr. B. I learned a lot about Brauner!

Frances Hurwitz November 17, 2020

Thanks Beverly on the article. Although not a fan of Brauner , definitely admire your review and perspective of the artist as well as risk taking visit at City Parma which is my all time “go to” each time I am in Paris !

Barb Harper December 6, 2020

Beverly, You are amazing with your in depth articles. I, really, didn't know Brauner. Your introduction and details of is life made him and his art come alive for me. Thank you.