Figure 1Jeff Koons with Bouquet of Tulipes, Petit Palais, October 2019

Jeff Koons Goes to Paris

Review by Beverly HELD Ph.D

As you know, art museums and temporary art exhibitions are my thing, my beat. But today I want to talk about a sculpture that the United States presented to France as a memorial to the victims of the terrorist attacks of 2015. Anyone who was in Paris last fall or who follows the art scene or the Paris scene will know or vaguely remember what I am going to talk about here, Jeff Koons’ Bouquet of Tulips. Which you will find in the garden in front of the Petit Palais whenever you are allowed back here, which I hope will be soon.

A lot has been written about Koons’ gift to the City of Paris, a lot of it smart ass, not much of it smart. I want to talk about this gift’s evolution, historical context and intended placement. I will try to do it with more smart than smart ass (wish me luck !).

But first a word about Jeff Koons. I think it is fair to say that Koons is an artist people love to hate, except for the collectors who buy his work and the high end fashion houses, like Louis Vuitton, who commission him to create designs. (Figure 2) Jeff Koons either celebrates or appropriates (word choice determined by what you think of the artist) the art of his predecessors, among them Marcel Duchamp and his ready mades, (think for example, the Urinal, Figure 3), Claes Oldenburg and his oversized everyday objects, (think for example, the Giant Safety Pin, Figure 4) and Andy Warhol, (think for example, Campbell Soup Cans, Figure 5). Warhol too, was vilified by critics and fellow artists for successfully making art out of not art. Koons’ iconography is a celebration (or monetization for the haters) of popular culture, primarily, but not exclusively, American popular culture. With the Vuitton commission, his appropriations went directly to the art historical canon, to Leonardo, Titian, Rubens, Fragonard and Van Gogh, bringing at least two of these artists into the domain of popular culture, a place they hadn’t been for a while (maybe ever). So, was that a bad thing, I don’t think so. Those handbags may have introduced a lot of people to artists they may never have heard of otherwise.

Figure 2. Louis Vuitton Sac by Jeff Koons after ‘Young Girl and her Dog,’ Fragonard, 1772

Figure 3. A Urinal, Marcel Duchamp, 1917

Figure 4. Giant Safety Pin, Claes Oldenburg, 1999

Figure 5. Campbell’s Soup Cans, Andy Warhol, 1961

The commission? Oh, right, the commission. It came about this way. After the November 2015 terrorists attacks in Paris, most horrific among them (although they were all awful), the attack at the Bataclan Theater which left 90 people dead, the U.S. ambassador to France, Jane Hartley, (an Obama appointee) asked Jeff Koons to create an artwork for the United States to give to the City of Paris to honor the victims. I don’t know if Hartley discussed the idea with her boss before offering the commission to Koons or if any other artists were considered for the commission. Hartley, who was a bundler (a person who ‘bundles’ individual political contributions) for the Democratic Party, presumably wasn’t too worried about the finances. The gift was offered. The gift was accepted. The controversy began.

A number of misconceptions (as well as intentional misrepresentations) have dogged the commission from the beginning with artists and art professionals either imploring the French government to reject the gift or imploring the government to ignore the naysayers. https://www.artforum.com/news/leading-french-cultural-figures-urge-paris-to-accept-jeff-koonss-gift-74427

In an interview at the unveiling of the sculpture, Koons addressed a range of these issues from price to placement. Let’s start with price. The interviewer asked Koons how something can be called a gift if the recipient pays for it. Koons explained that he gave the concept as a tribute to the victims, but that the actual construction costs of the sculpture were always intended to be paid for by donors and the French government. And of course what he said makes sense. If a painter, for example, or a print maker for a better example, ‘gifts’ a painting or a print, the art work would be given by the artist to the recipient. Simple as that. But here we are talking about a huge public sculpture that had not yet been made. Koons explained that public monuments have traditionally been financed by individual and corporate contributions. He cited several examples, among them a public sculpture Picasso designed for the city of Chicago in 1963. (Figure 6) The cost of constructing the sculpture was about $2.8 million in today’s dollars, paid mostly by three charitable foundations. Picasso was offered payment for designing the piece but declined, stating that the concept was his gift to Chicago. Another example is the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty (the statue itself was a gift from France to the US) which was paid for by individual subscriptions in the U.S. (Figure 7)

Figure 6. ‘Chicago Picasso, Picasso Chicago 1967

Figure 7. Statue of Liberty base, New York, Frederic Bartholdi, dedicated 1886

The materials and production costs of Koons’ piece were initially projected at 3.5 million euros (about $4 million). The US Ambassador obviously had a list of potential French and Francophile donors to contact. According to Koons, when the final cost exceeded the projected cost, he contributed a $1 million of his own money. Koons has been accused of accepting the commission for its value as ‘product placement,’ presuming that Koons anticipated making a lot of money with all the ‘merch’ he would sell with the sculpture’s design on it. To that criticism, Koons explained that not only did he give three years of his life to the project and pay his staff to work on it, he also donated 80% of the design’s copyright to the families of the victims of the terrorist attacks and the remaining 20% to the city of Paris to maintain it. Cost addressed, cost explained. Next.

Let’s consider the sculpture itself and its antecedents, then circle back to placement. The sculpture is a polychrome aluminum coated bronze hand holding 11 tulips, each a different color or hue of blue, orange, green, white, red and yellow. (see above) The statue stands 41.4 feet high (12.62 m) and is 27.4 feet wide (8.35-m) and weighs 34 tons (68,000 pounds). When asked why the tulips are such bright colors, Koons reminded the interviewer that in ancient Greece, buildings and statues alike were painted in bright colors. And of course he is right and if Trump gets his way and all future federal buildings are designed in a classical style, one can only hope that each tympanum and triglyph; every metope and entablature will be painted in dazzlingly bright colors. (Figure 8) But for people who know Koons’ work, the tulips aren’t bright enough, they are mat, not shiny (see below) and when he was asked why, he stated it was out of respect for the deceased.

Figure 8. Color reconstruction of the Parthenon, Athens, Greece 438 BCE

When Koons was asked why the tulips are shaped like balloons, he said that for him, humans are like balloons, they inhale or inflate, they exhale or deflate. I had never thought of balloons in quite that way, and I am guessing maybe you haven’t either. But it is interesting and maybe gives another dimension to Koons’ fascination with them. When asked about the meaning of a bouquet, Koons said, ”I wanted to make a gesture of support and friendship between the people of the United States and France. …. Flowers are associated universally with optimism, rebirth ….. and the cycle of life. They are a symbol that life goes forward”.

I appreciate Koons’ patient responses to the interviewer’s questions. But they are more or less the same answer he has given about other balloons in his oeuvre. If you have a chance, listen yourself. https:/ judithbenhamouhuet.com/jeff-koons-in-paris-i-gave-three-yearsof- my-life-for-the-bouquet-of-tulips/ https://www.sortiraparis.com/artsculture/exposure/articles/178048-jeff-koons-bouquet-of-tulipson- the-champs-elysees-in-paris-pictures/lang/en

To state the obvious, Jeff Koons did not create the Bouquet of Tulips specifically for this commission. Tulip balloons are part of his Celebration series which he began working on in 1994 and which includes the Balloon Dog (Figure 9), Cracked Egg and Play Doh, etc. Koons created five gargantuan Tulip Bouquet Balloons and they are very shiny, mirror-polished, highly reflective stainless steel with transparent color coating. With no hand to hold them, they are displayed splayed on the floor, as at the Broad Collection in Los Angeles (Figure 10) or splayed on the ground, as outside the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. (Figure 11) An idea of the potential merch value of the Bouquet of Tulips Koons gifted to France, can be demonstrated easily enough - high end porcelain plates at Bernaudaud (Figure 12) and mass produced Puppies and Bunnies (Figure 13) available at museum gift shops everywhere.

Figure 9. Balloon Dog, Jeff Koons, Celebration series, 1995-2004

Figure 10. Tulip Bouquet, Broad Museum, Los Angeles, Jeff Koons, 1995 - 2004

Figure 11. Tulip Bouquet, Guggenheim Museum Bilboa, Jeff Koons, 1995-2004

Figure 12. Tulips, Bernardaud, porcelain, 2015, limited edition based upon Jeff Koons Tulips, 1995

Figure 13. Balloon Dog Bookends, Jeff Koons, Celebration series, 1995-2004

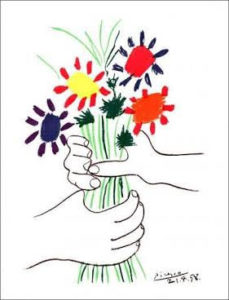

Koons cited a specific influence for his Tulip Bouquet, a lithograph by Picasso, entitled ‘Bouquet of Peace’. (Figure 14) Created for a 1958 peace demonstration in Stockholm, Sweden, Picasso’s Bouquet depicts two hands, simultaneously representing the act of giving and receiving, a call for peace and harmony.

Figure 14. Bouquet of Peace, lithograph, Pablo Picasso, 1958

Koons’ Bouquet is only one hand, the offering hand, a gesture of friendship and solace. The receiving hand is implied, it is the City of Paris, the people of France. I think it is a lovely gesture, especially from a country that owes its existence to the other and which accepted as a gift from that country not only military aid at its inception, but a statue to mark the centennial of its birth 100 years later. (Figure 15)

Figure 15. Statue of Liberty, New York, Frederic Bartholdi, 1886

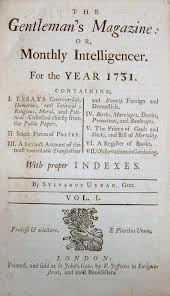

A hand holding a bouquet of flowers is not original to Picasso or Koons, of course. One example, among many is a hand holding a bouquet of flowers on the title page of an 18th century English journal, The Gentleman’s Magazine, a periodical well known to colonial Americans. (Figure 16) America’s founding fathers found the bouquet interesting as a motif, but they found the phrase next to the bouquet even more interesting. “E Pluribus Unum’, ‘From Many, One’ .

Figure 16. Frontispiece, Gentleman’s Magazine, 1731

For the Gentleman’s Magazine, the phrase went from the obvious, ‘From many flowers, one bouquet,’ to slightly more obscure, ’From many articles, one journal.’ On the Great Seal of the United States, designed by the fab three - Franklin, Jefferson and Adams - after they had gotten the Declaration of Independence out of the way, it means ‘From many states, one nation’ and the flowers were transformed into arrows held by the American Bald Eagle. (Figure 17)

Figure 17 Great Seal of the United States, adopted, 1782 original drawing, Pierre Charles L’Enfant.

There are 13 arrows in the eagle’s talons, each representing one of the original colonies. In Koons’ Bouquet of Tulips, there are eleven tulips, one short of a dozen. According to Koons, the missing flower represents the people who were killed during the terrorist attack, who can never return but whose memory is always present. To convey a sense of loss and history. And of course, the number twelve is an especially significant one. There are twelve hours in a day, twelve hours in a night, twelve months in a year, Christ’s apostles numbered twelve. So, a presentation that is obviously one short of a significant number will always reference what is missing.

About that hand. (Figure 18) When asked whose hand It was, Koons replied that the model was one of his assistants, a young woman. Why hers, because it is a celebration of youth, looking optimistically toward the future. Detractors have insisted that the hand is that of a white person. But the hand holding Koons’ Bouquet is not the flesh color in my box of Crayola crayons back in the day. Depending upon the light, the hand has a reddish, or brownish, or yellowish hue, suggesting to me at least the diversity that is America - Native American, Hispanic and Asian.

Figure 18. Hand holding Bouquet of Tulips, Petit Palais, Jeff Koons

My daughter, the hand model, whose porcelain perfection would have been just the ticket only a few years before she started modeling, has a harder and harder time getting gigs. Advertisers want a hand that suggests ethnic diversity, not white supremacy. I was at the Louboutin exhibition a while back. In one room, Louboutin’s flesh colored shoes and boots took center stage. Why? Louboutin explained in a blog post from 2016, “I’ve always done a Nude shoe but only using the color beige,” A team member finally told him, “beige is not the color of my skin”. “Nude” went from color to concept and Louboutin’s flesh heels range from “porcelain” to “deep chocolate”. (Figure 19) I think the hand holding Koons’ Bouquet is equally ‘woke’.

Figure 19. Christian Louboutin, Nudes Collection, 2016

The size of Koons’ Bouquet was based on the size of Statue of Liberty. And the placement of the hand and fingers of the Statue of Liberty determined the placement of the hand holding the Bouquet.

The Statue of Liberty is a significant model for several reasons, firstly of course because it was a gift from France to the United States honoring the 100th anniversary of American Independence. But it is also significant because of where Koons’ sculpture was initially going to be placed, in the forecourt of the Palais de Tokyo.

That placement would have been perfect, if we think of the long view down the Seine, starting at The Flame, (Figure 20) which is a full scale replica of the flame held by the Statue of Liberty, on Pont Alma, now known as Diana’s Square, to Koons’ Bouquet of Tulips on the forecourt of the Palais de Tokyo and finally to the replica of the Statue of Liberty on the manmade Isle aux Cygnes, just under the Pont Grenelle. (Figure 21) Three statues, three references to the amity between the United States and France.

Figure 20. The Flame of Liberty, Place Diana, Pont Alma, 1989

For those of you not familiar with either the Flame of Liberty on Pont d’Alma or the replica of the Statue of Liberty on the Isle aux Cygnes, this is for you. The Flame of Liberty was given to the city of Paris in 1989 by the International Herald Tribune to celebrate the newspaper’s 100th anniversary (1987) of publishing an English-language daily newspaper in Paris. It was paid for by donors. On the base of the monument a commemorative plaque reads: 'The Flame of Liberty. An exact replica of the Statue of Liberty's flame offered to the people of France by donors throughout the world as a symbol of the Franco-American friendship. On the occasion of the centennial of the International Herald Tribune. Paris 1887–1987”.

The replica of the Statue of Liberty on the Isle aux Cygnes, (a tiny island accessible only at Pont Bir Hakim and Pont de Grenelle) is one of five replicas of the Statue of Liberty in Paris (six if you count the micro one on the statue at Place Michel Debré – I don’t). It is the largest and it was given to the City of Paris in 1889 by the American community in Paris to commemorate the centennial of the French Revolution. Oddly, for a group of Americans living in Paris, who should have known better, the statue was officially dedicated on July 4th rather than Bastille Day, July 14. The statue’s plaque does bear both dates July 4, 1776 and July 14, 1789. The gift was given to celebrate the close bond between France and the United States, and to ‘reaffirm the dedication of the two nations to the republican ideal on which they were founded’. https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/statue-of-liberty-pont-de-grenelle

There are a few interesting parallels and synchronicities that I want to mention here as we try to put Koons’ sculpture into perspective.

Eye Sore to Icon:

Figure 21. Statue of Liberty, replica, Isle des Cygnes, dedicated 1889

The Eiffel Tower (Figure 22) has become a beloved Parisian icon. But initially it was called a hideous factory chimney. The 19th century art critic Karl Huysmans thought it looked like a suppository with holes.

The Louvre Pyramid (Figure 23) is now acknowledged as a brilliant solution to what had been a vexing problem of space and light. Initially it was derided as “an architectural joke, an eyesore, an anachronistic intrusion of Egyptian death symbolism in the middle of Paris” (NYTimes, 1985).

Try again:

Frederic Bartholdi, the sculptor who designed the Statue of Liberty, originally offered the statue to Egypt to be placed at the entrance of the Suez Canal. (Figure 24) The Egyptians weren’t interested. So Bartholdi kept looking and finally sold the idea of a nearly identical statue, now called the Statue of Liberty, to France which bought it to present to the United States on the 100 anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

Figure 24. Sketch for Statue for Suez Canal, Egypt, Frederic Bartholdi, 1860s

I.M. Pei, the architect of the Louvre pyramid, tried to sell his pyramid scheme to other institutions, some bought (IBM in 1984), others didn’t.

Not here you don’t:

Jeff Koons’ Bouquet of Tulips isn’t the first public art work forced to find another location. The Flame of Liberty was supposed to be placed on the Place des États-Unis, but Jacques Chirac, mayor of Paris at the time, objected to that location. The Flame finally found a home near the intersection of Avenue de New-York and the Place de l'Alma. In 1997, immediately after the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, in the tunnel beneath the Pont d’Alma, the Flame became her unofficial memorial. Now, many people think this sculpture was erected in her memory. In 2019, the Flame finally did become her official shrine and Place d’Alma is now Place Diana.

In Summary

Jeff Koons’ Bouquet of Tulips reuses an idea he had already developed, but so too does Bartholdi’s Statue of Liberty and I.M. Pei’s Louvre Pyramid. And while Koons’ Bouquet of Tulips is pilloried now, so too were the Eiffel Tower and the Louvre Pyramid when they were initially built. And finally, there is precedence for not permitting a monument to be placed where it was originally intended. In the case of the Flame of Liberty, its current placement has added immeasurably to its significance. All I am saying here is that it is easier to react than to think, easier to reject than to appreciate.

4 comments

Julia Frey July 28, 2020

This is your best article ever! A confirmed Koons-hater, I've now got a much better idea of what he's about. Thanks to your meticulous and subtle explanations of the context I can respect the seriousness of his work, his personal integrity and his generosity. (He probably would not like my work either.)

Deedee Remenick July 28, 2020

ITS LIKE GOING TO "SCHOOL" LEARNING ALL OF THE FINER DETAILS BEHIND THE SUBJECTS YOU WRITE ABOUT. THANK YOU. Deedee Remenick

Mike July 28, 2020

Very well done. Keep them coming.

Joseph Francis Meltzer July 29, 2020

I am not an admirer of Jeff Koons. But I am sensitive to the gesture of friendship that the Americans offered to the French. And, even though the “gift” was commissioned and partly payed for, the Artist should be commended for his effort and generosity.