Figure 1. Exhibition poster. Regards sur la vie quotidienne, Cluny Museum, 2020

I saw a really interesting exhibition the other day at the Cluny Museum which I want to tell you about. But before I get to that, I wonder if you noticed the synchronicity between James Tissot who we talked about a few weeks ago and Christo about whom we spoke last week? Both of their fathers owned textile companies. Tissot’s French father sold luxury fabrics. The evidence of his son’s appreciation for all the gorgeous tissu is his handling of the exquisite dresses his comely sitters wear. Christo’s father owned a textile factory in Bulgaria, I’m guessing utilitarian material for a 20th century Communist country. There must have been reams of it around when Christo was growing up. All to support the State. Christo found a way to use bolts of it to celebrate freedom, his and ours. Interesting, no ?

Okay back to the exhibition at the Cluny Museum, home as I am sure you know, to the Lady and the Unicorn Tapestries. Which require a visit, obviously. So I did. Here is one image of a unicorn staring at its visage, Vanitas ? No, Sense of Sight. (Figure 2) Back to the exhibition. The title, ‘Regards sur la vie quotidienne,' (Insights into every day life) doesn’t specifically say everyday life in the middle ages, but this is more or less assumed since the Cluny is France’s National Museum of the Middle Ages. I know a bit about the middle ages since the Dordogne, where I have spent almost every summer of the past 25 (gosh, is it 25 already?) is awash in medieval-ness. My house is in the countryside but very close to a bastide. Which is ? Well, bastides were built during the Hundred Year’s War, (1337-1453) which England and France fought for the territory of the Aquitaine, that swath of land along the western seaboard of France. The English laid claim to it because Eleanor of Aquitaine who was first married to Louis VII, he was the spare [think Prince Harry] to the heir [think Prince William] to the French throne and when his older brother died unexpectedly, Louis became the unlikely and unhappy king. Eleanor could stand about 10 years and two daughters of it, before she, in a gesture Princess Diana would follow nearly 850 years later, dumped her king. But Eleanor left with her dowry intact, that is all the land of western France that she brought with her to her first marriage, was still hers when she married her second husband, Henry II, the king of England. And that dear friends is why both England and France claimed the Aquitaine as their own.

Figure 2. Lady and the Unicorn tapestry, Sense of Sight, detail, Paris, 1500.

Oh right, bastides. Bastides are medieval planned towns which dot the landscape of southwest France. (Figure 3) During the One Hundred’s Year War, whenever English troops gained territory or whenever the French did, they would plop a town down as a place holder, a bastide. Built on a grid plan, at their center was neither a church nor a chateau but a market. Around the market square were plots for houses. Each person who came to live in a bastide received a small parcel of land inside the bastide on which he had one year to build his house. He also received a much larger parcel of land outside the bastide on which to grow crops. A big appeal of the bastides is that they were granted the right to hold a weekly market at which the inhabitants could sell their crops and merchants to sell their wares. The bastide near where I live in the Dordogne has been holding a market every Thursday morning since 1270.

Figure 3. Monpazier, bastide in Dordogne, founded in 1285, central market square

Where did the peasants come from to populate the bastides? They were the same peasants who labored as farmers on estates owned by a lord. Have you ever heard of the Droit de Seigneur? ('Lord's Right'), also known as 'right of the first night’ ? It was a legal right in medieval Europe which allowed feudal lords to have sexual relations with a bride on her wedding night. Whether the lord acted on this right or not, it smacks of ownership and let a young man and his bride know exactly what they were on the lord’s land - chattel. So even with all the uncertainty of growing and selling their own crops, the idea of independence on bastide certainly appealed to a considerable number of peasants when they were offered the opportunity.

My home is a pigeonnier, (mine dates from the 16th century) a tall narrow stone structure with tiny windows, holes, really, at the top. (Figure 4) The holes are large enough for pigeons to fly in and out. And when they flew in, they roosted and while they roosted, they pooped. The guano is such good fertilizer that it often figured in a young woman’s dowry. Pigeons presented a big problem for peasants who farmed the estate of a lord. Pigeons were marauders, they ate the grain in the field, the stole the peasant’s grain. And the peasants could do nothing to stop them because only the lord and his family were permitted to eat pigeons. Peasants could not get ride of them and they couldn’t eat them either. During the French Revolution an enormous number of pigeonniers in France were destroyed as hated reminders of the detested aristocracy. But it is true that the farther away from the center of power, aka Versailles, the less powerful the lords were, the more in touch they were with the locals and that is why pigeonniers still dot the countryside in SW France and why I am the proud owner of a pigeonnier that has been completely restored (no pigeons).

Figure 4. Pigeonnier with pigeon holes.

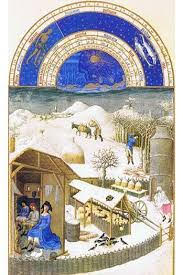

Back to the exhibition. I thought it was going to be like the Les Tres Riches Heures de Duc de Berry created by the Limbourg Brothers in 1415. Do you know it ? It is a Book of Hours, a collection of prayers for a lay person arranged so that s/he could know what prayers to recite at what time of day. This sumptuous book, the most famous example of Western European medieval manuscript illumination, is in the Musée de Condé at the Chateau de Chantilly. An illuminated manuscript is one which have decorative initial letters on each page and elegant border decorations. These decorations can be filled with abstract patterns, or vegetal ones or animal ones or historiated (illustrated scenes) ones. Just as you find in column capitols in medieval churches, especially cloisters. (Figure 5) As you look at the small and smaller paintings which decorate this gorgeous manuscript, you get a window into European life in the middle ages. That is especially true for the calendar images, which offer vivid representations of peasants doing back breaking work and elegantly attired aristocrats swanning about doing, well not doing anything, well, at least nothing useful. My two favorite calendar pages in the series, although I love them all, are January and February. January (Figure 6) depicts the exquisitely dressed Duc de Berry in blue, in profile, sitting behind a dining table groaning with the weight of food and scampering petits chiens. He welcomes his equally well dressed guests who arrive to feast and to exchange New Year’s gifts. In the February page, (Figure 7) we glimpse into a peasant’s house (hovel). Even though there is snow on the ground and it must be bitter cold, the door is open, the fumes from whatever they are burning for heat must surely have been foul smelling. The woman in the foreground spreads her legs in front of the fire, her skirt covers her knees and protects her modesty. The man directly behind her whose ‘equipment’ is visible to all and the woman behind him equally unencumbered by underwear, show no modesty at all. Outside men are tending to the animals and land. While you can’t see the original if you go to the Musée Condé, you can see a facsimile and you can go to the cafe and order dessert with Creme Chantilly which some think was invented here. The Chateau is not very far from Paris, after St. Denis, which you must visit and before the Abbaye de Chaalis about which we spoke a few weeks ago.

Figure 5. Historiated Column Capitals, cloister, Abbaye de St Pierre at Moissac, 11th C

Figure 6. February. Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, Limbourg Brothers, 1415

Figure 7 February. Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, Limbourg Brothers, 1415

Where was I, oh right, the exhibition at the Cluny. As I entered the exhibition, I was humming that song from Camelot, “What do the simple folk do, To help them escape when they’re blue”. But I soon found out that this exhibition is not about that, not at all. I guess railing against inequality, demanding social justice isn’t on everyone’s mind. Well, it certainly was not on the agenda for this exhibition. The exhibition looks at quotidian life, high and low, stressing the similarities and not dwelling on the egregious differences. And because you have been so patient, I am going to tell you about a few of the seven categories of daily life that the curators chose to discuss and illustrate and that I found particularly interesting. Here are the categories: Living, Dining, Bathing, Reading / Writing, Playing, Measuring, Praying.

Let’s start with Dining. We all know that Catherine de Medici brought forks to France when she arrived from Florence to marry the future Henri II in 1533. Have you ever been invited to a picnic in France and told to bring your own couverts ? Coming from the land of all things disposable, aka the USA, I have always found that a bit odd. Why not just provide plastic cutlery ? Well this exhibition provides the answers. We already know there were no forks, but here we learn that everyone traveled with their own spoon and knife. (Figure 8) Also there were no plates. You put whatever food was on offer on a tranche (slice) of bread and I suppose cut it with your knife and ate it with your spoon. Or maybe just picked it up with your hands and ate the bread/plate as you ate whatever you had piled on it. If the bread-plate was anywhere near as good as Ethiopian injera, count me in. Have you had Injera, a sourdough kind of pancake with a spongy texture. I became a fan of Ethiopian food when I lived in Washington, D.C. (Smithsonian Fellowships). Did you know that there are more Ethiopians in the Washington, D.C. area than anywhere outside of Ethiopia ? Anyhow, when you eat Ethiopian style, deliciously seasoned food sits on injera pancake plates. You use additional injera to pick up the food. What’s left of the injera plate after the food has been eaten is especially seasoned and delicious. Personal cutlery, odd yes, doable, definitely. But I found something else to be particularly alarming, even if my current sensibilities were not informed by Covid-19. Drinking vessels were communal! Not being a fan of backwash, I don’t think I would have managed sharing a cup. The only concession to rich vs poor in the exhibition is the quality of spoons and knives and drinking vessels. Since those used by poor people would have been of poor quality. So, we learn that the same implements for dining were used by wealthy and poor, alike, but the only surviving examples are those made of luxury materials, used by the wealthy.

Figure 8. Medieval knives, some with carved ivory handles

Let’s move on to bathing. The French are renown for their perfume and just as renown for why they need it. The myth (reality?) is that they don’t bathe, or at least they don’t bathe enough. But we can’t blame it on the middle ages. As it turns out, people in the middle ages did bathe. Wealthy people had their own baths, poor people bathed in public baths. (Figure 9) I had always wondered about that. Have you been to Ronda, in Spain ? If you walk down umpteen steps you are rewarded with one of the best surviving examples of an Arabic hammen, water baths, in Spain. There are three main rooms, one each for hot, medium and cold water. I kept wondering why Christians had lost their way when it came to bathing. Turns out it was a pandemic, worse than the one we are suffering through now, the plague, that got people thinking that bathing could be harmful to a person’s health. The medical theory was that if disease was spread by bad air and if water opened the pores to the air, then people were getting sick from taking baths. Epidemics like the Black Death seemed to confirm medical theories that bathing was dangerous. It was during the Renaissance and later that perfume and changing clothes more frequently helped combat people’s natural odors. (just for the record: horses sweat, men perspire, women exude) King Louis XIV, the Sun King who was born in 1638 and died in 1715 and who reigned for 72 years, was terrified of bathing and allegedly only took three baths during his long life. He was convinced that the less one bathed, the less likely one was to get sick. Yet, according to the Perfume Society, “Versailles was seriously fragrant. Throughout the Palace, bowls were filled with flower petals, to sweeten the air. Furniture was sprayed with perfume. Visitors were sprayed with perfume, on entering the Palace.” That’s one way to do it, I guess.

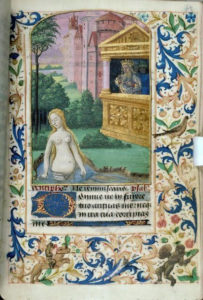

Figure 9. Wealthy medieval bathers, illuminated manuscript page

I found all of this bathing information very interesting because I had always assumed that paintings of naked women bathing in a garden, from Susanna and the Elders which depicts a young married woman being ogled at by two dirty (metaphorically speaking) old men (Figure 10) to Bathsheba at her Bath (being ogled at by King David) (Figure 11) was primarily for prurient purposes. Since bathing was the done thing throughout the middle ages, images of nude bathing women, created up until the middle ages would be a reflection of societal customs. During the Renaissance and afterwards, I think we can safely say prurient rather than practice.

Figure 10. Susanna and the Elders, medieval illuminated manuscript page

Figure 11. King David watching Bathsheba at her Bath. Medieval illuminated manuscript page

Auxiliary to bathing is body care. In one display case I saw a selection of ivory ear cleaners. (Figure 12) Of all the orifices on the human body that deserve attention, I am talking about cleaning here, of course, the ear would seem relatively low on the list. And yet, here they were, ‘cure-oreille’ some with beautifully carved handles. I guess poor people used sticks.

Figure 12. Ear Cleaner, ivory, 1400

Let’s move on to Living, specifically furniture. Do you know what the French word for furniture is. Yes, meuble and buildings are called Immeuble. Meuble means movable and immeuble means unmovable. Furniture moves, houses do not. (unless you live on the San Andreas Fault, but that is another story) This category certainly concerns only the wealthy. How many poor people either then or now have multiple homes? Furniture had to be transportable and often collapsable (Figure 13) because the nobles who owned all these homes moved from chateau to chateau during the year and brought their furniture with them. Sort of establishes a context for George Bush, fils taking his pillow with him when he traveled. In addition to collapsable tables and chairs, there were lots of chests, (Figure 14). As the most common piece of furniture in a medieval household, they were used for storage. According to the Ménagier de Paris, a guidebook for housewives written at the end of the 14th century, ‘nothing should be left lying around on the floor’. Good advice, if people come to visit unexpectedly, or if your husband returns unexpectedly, all a housewife has to do is open the chest and toss whatever is lying around it, into it and nobody needs to see that chaos. Not exactly the Marie Kondo sensibility of tossing out what you don’t need, but rather a philosophy of tossing in what you don’t want seen.

Figure 13. Medieval collapsible table

Figure 14. Medieval oak trunk

The playing section shows card games for adults, doll house accessories for little girls and toy soldiers for little boys. (Figure 15) The reading / writing section includes a carving of boys in a school setting where absolutely no social distancing is taking place. (Figure 16) The carving suggests a rough and tumble learning environment that seems a lot more practical than medicating little boys for their exuberance. The measuring section shows ways to measure time, so people knew when to pray, knew how long to work. Weight and volume measures enabled a peasant farmer to actually see how much he owed his lord. (Figure 17) And weighing fruits and vegetables sold at the Bastide’s weekly market enabled the farmer to charge accurately and pay (or avoid) his taxes. Measurements were not standardized, not even between villages let alone countries. I wish you could have come to see this exhibition with me and we could talk about it, over a cafe afterwards, but alas, it will be closing at the end of September as will the Cluny itself. But the museum is scheduled to re-open next fall. I don’t think it is too early to start planning your visit to coincide with Christo’s wrapping of the Arc of Triomphe and the reopening of the Cluny, do you ?

Figure 15. Medieval dollhouse accessories and toy soldiers

Figure 16. Teacher with little boys at school, medieval carving

Figure 17. Medieval tithing measure, beautifully decorated with dancing girls

3 comments

Deedee Remenick August 11, 2020

ANOTHER GREAT AND INFORMATIVE ARTICLE.

Dolores Lilley August 11, 2020

As always I enjoyed reading this article. If I return from Canada by the end of September and make it before the closing of the exhibition I’ll you join me for a cafe after?

Terrance Gelenter August 14, 2020

absoulutely