JMW Turner at the Musee Jacquemart-Andre, Review Renewed.

Review by Beverly HELD Ph.D

My first review of the Turner exhibition at the Musée Jacquemart-André appeared after I had seen the exhibition ‘virtually’. I offer this modified review now, now that I have seen the exhibition ‘really’. The Musée Jacquemart-André was one of the first museums to reopen after the confinement. You will not be surprised that I was one of the first to visit the museum once it opened. Online tickets were (and still are) mandatory. I stood, masked, in a socially distanced line, on the sidewalk, on Boulevard Haussmann, waiting to gain entry. It was a brave (or frightening, depending upon your point of view) New World and we were all still finding our way in it. The guards, masked, were a little less laid back, a little more officious, which was good, which was as it should be. Once inside the staff was warm and welcoming. Since we were all masked and compliant with the new rules as we, staff and visitors, understood them, the vibe was peaceful and serene, so different from news reports I see and accounts I read of what is happening elsewhere.

I visit the Jacquemart-Andre 2 or 3 times a year. Always in conjunction with a temporary exhibition, sometimes in conjunction with a visitor who hasn’t been or hasn’t been in a while. So my sense of joy and relief on entering the museum was not because this particular museum is particularly important to me. It was simply because, I think, I had been denied entry for so long. Before going to see the exhibition, I wandered into the private apartments of Monsieur et Madame. (Figure 2) I walked along the Tiepolo fresco and lingered in the Music Room (Figure 3) which had, as usual, classical chamber music playing. I was brought nearly to tears by the normalcy of it all, a normalcy that I had sorely missed for the previous two months.

Figure 2. Nelie Jacquemart’s bedroom. Musee Jacquemart-Andre

Figure 3. Music Room, Musee Jacquemart-Andre

So how was the exhibition and how did it compare with its virtual iteration? (Figure 4) The exhibition was great and nothing can compare with the sheer joy of seeing paintings and watercolors ‘live’. The curators had done a wonderful job in presenting the exhibition online. But seeing the galleries and experiencing the exhibition in space as well as time, was as you might expect, sublime.

As I wrote in my review of the virtual exhibition, before we knew if or when museums in Paris would be reopening, and whether or not exhibitions scheduled would be scrapped or could be postponed, I was worried that this exhibition on Turner was going to be jam packed with too much stuff. As you probably know, I hate too much of anything, including Turners, maybe especially Turners. But this exhibition curated by Culturespaces, which is responsible for mounting two temporary exhibitions here each year, did a masterful job of limiting the scope and enhancing the depth of the exhibition. There was just enough stuff to prove the points the curators were making. And it could have been so different since JMW Turner, the great 19th century English artist whose watercolors and paintings presaged Impressionism, seems never to have thrown anything out - doodles, sketches, drawings, whatever. And this exhibition could have been a kitchen sink kind of affair because it is being held in conjunction with the Tate Britain which holds the largest collection of Turners in the world. The guy never threw anything out, period. I was at the Andy Warhol museum a couple of years ago and he was the same. Apparently at the end of every day, Warhol just slid whatever was on his desk into that week’s box. There are walls of those boxes at that museum. Ditto for Turner, but his, sometimes moldy, often brilliant, detritus is part of the huge Turner collection at the Tate Britain.

Reminiscing about the past, do you remember when I reviewed the Cezanne exhibition at the Monet Marmottan ? It was the last actual exhibition I was able to review before the confinement; a little show with new ideas - the influence ON Cezanne OF 16th century Italian artists and the influence OF Cezanne ON 19th century Italian artists. Paintings were selected to make their points and they did. The Turner exhibition at the Jacquemart-Andre is similarly intended. It is a small exhibition, 60 watercolors and 10 oils, spread over eight themes. And while Turner is always credited with having anticipated Impressionism, as this exhibition shows, he was a man of his time. A strange man, but a man of his time nonetheless. And it wasn’t as if his impressionistic watercolors had any influence on the impressionists, those watercolors were literally buried at the bottom of cartons, awaiting discovery.

This exhibition is about Turner the artist and not about Turner the man, which is just as well since he was definitely on the spectrum. His mother exhibited signs of mental illness from the time Turner was 10 years old and when she was finally admitted into an institution for the mentally ill, he was 24. (Figure 5) That same year, 1799, his father who had made his living as a barber, moved in with Turner and lived with him for the next 30 years as his son’s assistant. Turner never married but he did father two daughters by his long suffering housekeeper, or those girls may have been fathered by his father, or maybe, never mind, let’s not go there. The film ‘Mr Turner,’ which was released in 2014 to some acclaim, portrays Turner as the eccentric curmudgeon he was acknowledged to be. See the film, although I don’t think it will make you a Turner fan if you aren’t one already.

Figure 5. Turner, self portrait, 1799

The medium most associated with Turner is watercolor. It is a technique that is often not given much respect, dismissed as suitable for professional artists’ sketches and for amateur hobbyists’ efforts. I used to give tours at a paper mill, a moulin, in the south of France, that made watercolor paper by hand. After the tour, visitors could buy ‘carnets de voyage’ little bound books of handmade paper with a tiny traveling brush and tiny dabs of watercolor paints. Amongst the cartons Turner left to the British nation were lots of carnets de voyage. (Figure 6) These private and experimental works were made, according to the writer John Ruskin, for Turner’s ‘own pleasure and delight.’

Figure 6. Turner, carnet de voyage, 1828

The exhibition at the Musée Jacquemart-André includes examples of Turner’s private and experimental works alongside paintings intended for the public. By juxtaposing watercolors with oil paintings, sketches with finished works, the exhibition offers the visitor a glimpse at how the informal and private informed the finished and public. Divided into eight sections, each has a point to make and a few well chosen watercolors and oil paintings to make it. If you get here by January 2021, you will be able to see this exhibition for yourself. Here is a preview of what awaits you.

Section One will be a surprise for most Turner fans since his earliest surviving sketches are architectural studies and exercises in perspective. (Figure 7) At fourteen, Turner began taking classes in perspective and topography at the Royal Academy of Art, useful choices for a young lad earning his keep as an architect’s draftsman. As soon as he could, Turner began traveling during the summer months, sketchbook in hand. Turner was no plein air artist. He sketched outdoors and painted indoors. Where did he go on his earliest annual peregrinations? Well, maybe the sun never set on England’s Empire, but war with France meant that the Continent was off limits, so he traveled around England from Wales to the Scottish Highlands.

Figure 7. Turner, perspective study, House

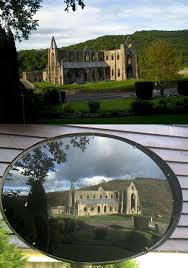

Section Two begins with a trip Turner took to the Swiss Alps and to Paris where he went to study the Old Masters at the Louvre.The Treaty of Amiens (1802-03) between England and France made that trip possible but Turner had to wait another 15 years, until the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, before he could travel to the Continent again. He concentrated instead on his Liber Studiorum (‘Book of Studies’) based on his watercolor designs which demonstrate categories of landscape ranging from the natural to the ideal. (Figure 8) Turner created his book as a way to promote himself as a worthy descendant of Claude Lorrain, (Figure 9) the 17th century French landscape painter who spent most of his life in Italy and whose picturesque paintings were all the rage in England when Turner was a young man. An 18th century English fan of Claude’s invented the ‘Claude Glass’ so that Claude loving English aristocrats could roam the English countryside looking for views, in nature, that resembled Claude paintings. Of course no such views existed, that is why God created artists. But these Englishmen had their trusty Claude glass to perform the miracle. To use the mirror, travelers would come upon a scene and tell their coachman to halt. Then they would turn their backs to the scene and hold their mirror shoulder height. Angling it so they could see behind them, the mirror performed its miracle. Its convex shape made distant objects look farther away and the mirror’s tinted glass softened the reflected tones. (Figure 10) I read an article on selfies recently. The author contends that the Claude glass was a precursor of the selfie, minus the self but with looking away from the view and into the camera with filters to render it artistic !

Figure 8. Turner, Liber Studiorum, 1809

Figure 9. Claude Lorrain, Pastoral, 1626

While the Turner we know and admire may not seem especially close to what can be achieved with a Claude glass (Figure 10), a link between Turner and a contemporary artist, Philip de Loutherbourg, seems more obvious. Loutherbourg’s invention was the Eidophusikon, a miniature theatre based on his own stage set designs. The Eidophusikon is a set of transparent colored lantern slides which create the illusions of time passing - green leaves turn red, the moon rises and lights the edges of passing clouds. (Figure 11) Loutherbourg took his Eidophusikon to a party at William Beckford’s mansion, Fonthill Abbey in 1781. Twenty years later, Turner was invited by Beckford to paint there.

Figure 10. Claude glass

Figure 11. Philip de Loutherbourg, Eidophusikon

Sections Three and Four concentrate on Turner’s travels which didn’t really begin until Turner was 44, in 1819, when he took his first Grand Tour of the Continent. Turner stayed in Italy for six months, mainly in Rome, studying classical monuments. He squeezed in two side trips, one to Naples, one to Venice. The intensity of light in southern Italy made a lasting impression on the artist who was already changing the way he depicted light and color. Turner travelled through France too, along the Rivers Seine and Loire. He made pencil outlines on site which he later transformed into watercolors and gouache on tinted paper. Engravings followed and these were sold as travel books. Turner’s pattern was to travel and sketch during the summer, work on and finish up in the winter. Repeat.

Section Five is about technique, specifically about Turner’s full scale color studies. The wall notes suggest that these studies, called ‘Color Beginnings,’ (Figure 12) must have pleased the artist because so many of them survive. Since he never threw anything out, I’m not sure there is much of an argument there. But, now we know, more or less, how Turner worked. He would go somewhere and make quick sketches of scenes that pleased him. Then he would go back to his boarding house or hotel room and make more detailed drawings based upon his prodigious visual memory. His ‘Color Beginnings’, full scale sketches, based upon his small, detailed sketches, were the next step. In many of these sketches, broad washes of color are detectable just beneath the surface of more delicate watercolors. Turner could never have imagined exhibiting these watercolors as finished paintings. His contemporaries wouldn’t have put up with it. Impressionists had a hard enough time exhibiting their paintings as finished works, and they were in oil. But we look at those full scale sketches by Turner with our post impressionist eyes and sensibilities. We appreciate, indeed expect, a certain unfinished quality. It is why the paintings by artists like James Tissot seem to our eyes, forced, stale, even overworked. Turner was never satisfied, he was always reworking his ‘Color Beginnings’. It was the same with his oil paintings. In the film ‘Mr Turner,’ you see Turner, at the Royal Academy, after all the paintings had been hung for exhibition, on what was called ‘Varnishing Days.’ There’s Turner, walking around with a leather satchel filled with paints and a palette knife, applying unifying dabs of detail here or there bringing it all together. Turner was like a chef, still adjusting seasonings and presentations even as the waiter takes a plate to the waiting diner.

Figure 12. Turner, ‘Color Beginning’ 1818

Section Six is completely unexpected. It shows Turner at his patron’s home, that is at Petworth, in Sussex, at the estate of Lord Egrermont. We are treated to little watercolor sketches which Turner made of the house and the people who lived there. (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Turner, Petworth, watercolor, 1827

Sections Seven and Eight celebrate the last decades of Turner’s life, during which he painted some of his finest watercolors. Two events came together to permit Turner to become ‘Turner’ - his clientele changed and so did taste. His work was sought after by a small group of connoisseurs which freed Turner from having to produce for exhibitions or publishers. And he took a third and final trip to Venice in 1840, from which he produced a wealth of watercolors and a collection of canvases. La Serenissima - magical light, shimmering reflections off the lagoon, dissolving phantom-like architectural forms. One of the oil paintings from this period prompted a critic to proclaim Turner a ‘magician’, with ‘command over the spirits of Earth, Air, Fire and Water’. (Figure 14)

Figure 14. Turner, Venice

I have been rereading John Berger’s, ‘About Looking,’ (1980) a slender volume which if you don’t know it, you should try to read it. If you do know it, read it again, it is that good. Here is a snippet of Berger’s thoughts on Turner, the son of a barber who lived during the Industrial Revolution. “Consider,” writes Berger, “some of his later paintings and imagine, in the backstreet shop, water, froth, steam, gleaming metal, clouded mirrors, white bowls or basins in which soapy liquid is agitated by the barber’s brush and detritus deposited. Consider the equivalence between his father’s razor and the palette knife which Turner insisted upon using so extensively. More profoundly - at the level of childish phantasmagoria - picture the always possible combination, suggested by a barber’s shop, of blood and water, water and blood.” Berger continues, “Turner lived through the first apocalyptic phase of the British industrial revolution. Steam meant more than what filled a barber’s shop. Vermilion meant furnaces as well as blood. Wind whistled through valves as well as over the Alps.” Wow! Turner’s childhood memories and the Industrial Revolution. Claude Lorrain and the Eidophusikon. None could predict the artist Turner would become but they can give us some insights into the multiple strains of his genius. I’m glad I saw the virtual exhibition, even happier I saw the ‘real’ one and delighted to have been able to share them both you with ! Fingers crossed you will get here by January 2021 to see the exhibition yourselves.